How Is Active Transport Different From Facilitated Diffusion

Juapaving

Mar 14, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

How is Active Transport Different from Facilitated Diffusion?

Cell membranes are selectively permeable barriers, regulating the passage of substances into and out of the cell. This crucial control is achieved through various transport mechanisms, with active transport and facilitated diffusion being two prominent examples. While both processes involve the movement of molecules across the membrane with the assistance of membrane proteins, they differ significantly in their energy requirements and the direction of movement. Understanding these differences is fundamental to grasping the complexities of cellular physiology.

The Core Difference: Energy Expenditure

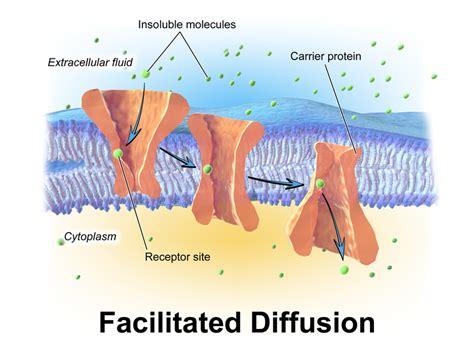

The most fundamental distinction between active transport and facilitated diffusion lies in their energy dependence. Facilitated diffusion is a passive transport process, meaning it doesn't require energy input from the cell. Molecules move down their concentration gradient, from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration. Think of it like rolling a ball downhill – it requires no external force. The movement is driven by the inherent tendency of molecules to disperse and reach equilibrium.

Active transport, on the other hand, is an energy-requiring process. It moves molecules against their concentration gradient, from an area of low concentration to an area of high concentration. This uphill movement requires energy, typically in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the cell's primary energy currency. Imagine pushing a ball uphill – you need to exert force (energy) to move it against gravity.

The Role of Membrane Proteins

Both active transport and facilitated diffusion rely on membrane proteins to facilitate the movement of molecules across the cell membrane. These proteins act as channels or carriers, providing specific pathways for molecules to traverse the hydrophobic lipid bilayer. However, the types of proteins involved and their mechanisms of action differ.

Facilitated Diffusion: Channels and Carriers

In facilitated diffusion, membrane proteins function as either channels or carriers.

-

Channels: These proteins form hydrophilic pores or tunnels through the membrane, allowing specific molecules or ions to pass through passively. They are highly selective, ensuring only particular molecules can pass. Examples include ion channels that allow the passage of ions like sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), and chloride (Cl−). The opening and closing of these channels can be regulated, influencing the rate of diffusion.

-

Carriers: These proteins bind to specific molecules on one side of the membrane, undergo a conformational change, and release the molecule on the other side. This process is still passive; the carrier protein simply facilitates the movement down the concentration gradient. The binding and release of the molecule are driven by the concentration gradient, not ATP hydrolysis. Glucose transporters are a classic example of carrier proteins involved in facilitated diffusion.

Active Transport: Pumps

Active transport utilizes protein pumps which are specialized membrane proteins that use energy, typically ATP, to move molecules against their concentration gradient. These pumps are often categorized based on the mechanism of energy coupling:

-

Primary Active Transport: This involves the direct use of ATP hydrolysis to drive the movement of molecules. The classic example is the sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+-ATPase), which pumps three sodium ions (Na+) out of the cell and two potassium ions (K+) into the cell for every molecule of ATP hydrolyzed. This pump maintains the electrochemical gradient across the cell membrane, crucial for nerve impulse transmission and other cellular processes. Other examples include the proton pump (H+-ATPase) found in the stomach lining and the calcium pump (Ca2+-ATPase) in muscle cells.

-

Secondary Active Transport: This type of transport indirectly uses ATP. It couples the movement of one molecule against its concentration gradient with the movement of another molecule down its concentration gradient. The energy stored in the electrochemical gradient of the second molecule (often established by primary active transport) drives the movement of the first molecule. This is also known as co-transport or coupled transport. There are two main subtypes:

-

Symport: Both molecules move in the same direction across the membrane. An example is the sodium-glucose cotransporter (SGLT1) in the intestine, which uses the sodium gradient (established by the Na+/K+-ATPase) to transport glucose against its concentration gradient.

-

Antiport: The molecules move in opposite directions across the membrane. An example is the sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX), which removes calcium from the cell by using the inward sodium gradient.

-

Specificity and Saturation

Both facilitated diffusion and active transport exhibit specificity. This means the membrane proteins involved are selective for particular molecules or ions. Only molecules with the correct shape and charge will bind to the carrier proteins or pass through the channels. This specificity ensures the controlled movement of essential molecules and prevents the passage of unwanted substances.

Furthermore, both processes can exhibit saturation. This occurs when all the available transport proteins are occupied, and the rate of transport plateaus even if the concentration gradient increases. In facilitated diffusion, saturation happens when all the carrier proteins are bound to molecules. In active transport, saturation occurs when all the pumps are actively working.

Rate of Transport

The rate of transport differs between the two processes. Facilitated diffusion is generally faster than active transport at low substrate concentrations. The rate of facilitated diffusion is primarily determined by the concentration gradient and the number of available transport proteins. As the concentration gradient increases, the rate of diffusion increases until saturation is reached.

Active transport, being energy-dependent, is generally slower than facilitated diffusion, especially at low substrate concentrations. The rate of active transport is determined by the number of available pumps and the rate of ATP hydrolysis.

Examples in Biological Systems

The differences between active transport and facilitated diffusion are vividly illustrated in various biological systems:

-

Nutrient Uptake: Intestinal cells absorb glucose from the gut lumen using the SGLT1 cotransporter (secondary active transport), while the uptake of some amino acids might involve facilitated diffusion.

-

Nerve Impulse Transmission: The establishment and maintenance of the resting membrane potential in nerve cells are dependent on the Na+/K+-ATPase pump (primary active transport), while the movement of ions during action potentials involves both facilitated diffusion through ion channels and active transport.

-

Kidney Function: The kidneys reabsorb essential molecules like glucose and amino acids from the filtrate using active transport mechanisms to prevent their excretion in urine. They also regulate ion balance through active transport and facilitated diffusion.

-

Plant Cells: Plant cells utilize active transport to maintain turgor pressure and accumulate ions against their concentration gradients.

Conclusion

Active transport and facilitated diffusion are distinct yet essential membrane transport mechanisms crucial for maintaining cellular homeostasis. While both utilize membrane proteins, their energy requirements and direction of movement are fundamentally different. Active transport requires energy to move molecules against their concentration gradient, while facilitated diffusion is a passive process driven by the concentration gradient. Understanding these differences is crucial for comprehending a wide range of biological processes, from nutrient uptake to nerve impulse transmission and kidney function. The interplay between these two mechanisms ensures the efficient and regulated transport of molecules across cell membranes, sustaining the complex functions of living organisms.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Is Air An Element Or Compound

Mar 14, 2025

-

Is The Square Root Of 13 A Rational Number

Mar 14, 2025

-

Explain Why Your Relation Is A Function

Mar 14, 2025

-

The Terminal Electron Acceptor In Aerobic Respiration Is

Mar 14, 2025

-

Whats The Difference Between Alternator And Generator

Mar 14, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about How Is Active Transport Different From Facilitated Diffusion . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.