What Is The Weakest Intermolecular Force

Juapaving

Mar 21, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

What is the Weakest Intermolecular Force? Understanding Van der Waals Forces

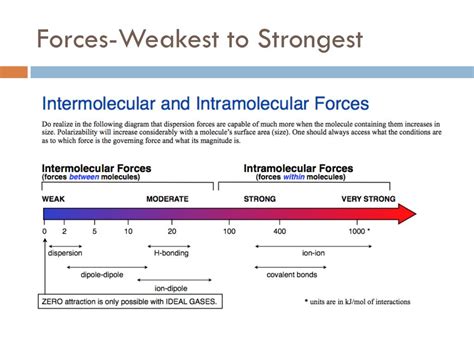

Intermolecular forces are the attractive or repulsive forces that act between molecules. These forces are significantly weaker than the intramolecular forces (bonds) that hold atoms together within a molecule, but they play a crucial role in determining the physical properties of substances like boiling points, melting points, viscosity, and solubility. Understanding these forces, particularly the weakest among them, is key to comprehending the behavior of matter. This article delves into the fascinating world of intermolecular forces, focusing specifically on identifying the weakest and exploring its impact.

The Hierarchy of Intermolecular Forces

Before pinpointing the weakest intermolecular force, let's establish the hierarchy. Intermolecular forces are generally categorized into three main types, each with varying strengths:

-

Hydrogen Bonding: This is the strongest type of intermolecular force. It occurs when a hydrogen atom bonded to a highly electronegative atom (like oxygen, nitrogen, or fluorine) is attracted to another electronegative atom in a nearby molecule. The strong electronegativity difference creates a significant dipole moment, leading to a powerful attractive force. Water's unique properties are largely attributed to its extensive hydrogen bonding network.

-

Dipole-Dipole Interactions: These forces exist between polar molecules – molecules with a permanent dipole moment due to an uneven distribution of electron density. The positive end of one polar molecule is attracted to the negative end of another. While stronger than London Dispersion Forces, they are significantly weaker than hydrogen bonds.

-

London Dispersion Forces (LDFs): Also known as van der Waals forces (a broader term encompassing all weak intermolecular forces), these are the weakest type of intermolecular force. They arise from temporary, instantaneous dipoles that occur due to the random movement of electrons within a molecule. At any given moment, the electron distribution might be slightly uneven, creating a temporary dipole. This temporary dipole can then induce a dipole in a neighboring molecule, leading to a weak attractive force. LDFs are present in all molecules, regardless of polarity.

London Dispersion Forces: The Weakest Link

The definitive answer is that London Dispersion Forces (LDFs) are generally considered the weakest intermolecular force. While hydrogen bonding and dipole-dipole interactions are stronger and more readily apparent, LDFs are ubiquitous. Their weakness stems from the temporary and fleeting nature of the induced dipoles. The strength of LDFs is significantly influenced by factors like:

-

Molecular Size and Shape: Larger molecules with more electrons have greater possibilities for instantaneous dipole formation, leading to stronger LDFs. A more elongated or extended shape also increases the surface area available for interaction, enhancing the LDFs.

-

Polarizability: This refers to the ease with which the electron cloud of a molecule can be distorted to create a temporary dipole. Molecules with highly polarizable electron clouds exhibit stronger LDFs.

Understanding the Transient Nature of LDFs

The ephemeral nature of LDFs is a critical aspect of their weakness. Unlike the relatively permanent dipoles in hydrogen bonding or dipole-dipole interactions, the temporary dipoles in LDFs constantly fluctuate. They appear and disappear rapidly, resulting in weak and short-lived attractive forces. This is why substances held together primarily by LDFs often have low boiling points and melting points, as less energy is required to overcome these weak forces.

Comparing the Strengths: A Closer Look

To better appreciate the weakness of LDFs, consider the following comparisons:

-

LDFs vs. Hydrogen Bonding: The difference in strength is dramatic. Hydrogen bonds are typically an order of magnitude stronger than LDFs. This explains why water (with strong hydrogen bonding) has a significantly higher boiling point than methane (with only LDFs) despite having similar molecular weights.

-

LDFs vs. Dipole-Dipole Interactions: While LDFs are weaker than dipole-dipole interactions, the difference isn't as vast as the comparison with hydrogen bonding. However, the presence of dipole-dipole interactions often overshadows the contribution of LDFs in polar molecules.

-

The Cumulative Effect of LDFs: Although individually weak, the cumulative effect of LDFs in large molecules can be substantial. In long-chain hydrocarbons, for example, the numerous LDFs contribute significantly to their physical properties, resulting in higher boiling points than might be expected based on their individual weakness.

The Importance of LDFs Despite Their Weakness

Despite their relative weakness, LDFs are incredibly important for several reasons:

-

Universality: They are present in all molecules, regardless of their polarity. Even polar molecules experience LDFs in addition to their stronger dipole-dipole or hydrogen bonding interactions.

-

Influence on Physical Properties: While not always dominant, LDFs contribute significantly to the physical properties of many substances, particularly nonpolar ones. The boiling points and melting points of nonpolar molecules are directly determined by the strength of their LDFs.

-

Solubility and Interactions: LDFs play a role in the solubility of nonpolar substances in nonpolar solvents. The interactions between solute and solvent molecules are largely governed by LDFs in such cases.

Applications and Real-World Examples

The influence of LDFs can be seen in many everyday phenomena:

-

The boiling point of noble gases: Noble gases, which exist as single atoms with only LDFs, exhibit very low boiling points, reflecting the weakness of these forces.

-

The viscosity of oils: Long-chain hydrocarbon oils have high viscosities because of the numerous LDFs between the long molecules. These forces create a strong internal resistance to flow.

-

The behavior of alkanes: The boiling points of alkanes increase with molecular weight, reflecting the increasing strength of LDFs as the size of the molecule increases.

Conclusion: A Fundamental Force in the Molecular World

While London Dispersion Forces are undeniably the weakest intermolecular force, their pervasive presence and contribution to the physical properties of matter cannot be overlooked. Understanding their characteristics – their temporary nature, dependence on molecular size and shape, and cumulative effect – is crucial for appreciating the intricate interplay of forces that govern the macroscopic behavior of substances. From the boiling point of helium to the viscosity of motor oil, the seemingly insignificant LDFs play a fundamental role in shaping the world around us. Their weakness is a key aspect of their overall importance in the study of chemistry and physics at the molecular level. Further research into the intricacies of these forces continues to provide deeper insights into the complexities of molecular interactions and material science.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Which Of The Following Are Not Trigonometric Identities

Mar 27, 2025

-

Why Are Most Ionic Substances Brittle

Mar 27, 2025

-

What Are Examples Of Unit Rates

Mar 27, 2025

-

What Is The Least Common Multiple Of 18 And 6

Mar 27, 2025

-

Which State Of Matter Has A Definite Shape And Volume

Mar 27, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Is The Weakest Intermolecular Force . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.