What Atmosphere Do Planes Fly In

Juapaving

Mar 19, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

What Atmosphere Do Planes Fly In? A Comprehensive Guide

Planes fly in the Earth's atmosphere, but not just any part of it. Understanding the atmospheric layers and how they affect flight is crucial to appreciating the challenges and marvels of aviation. This article delves deep into the atmospheric conditions planes encounter, from takeoff to landing and everything in between. We'll explore the different atmospheric layers, their characteristics, and how these characteristics impact aircraft performance and safety.

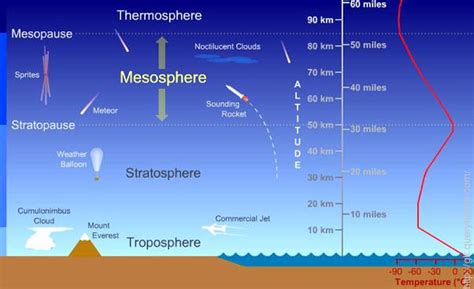

The Earth's Atmospheric Layers: A Flight Path Perspective

The Earth's atmosphere isn't a uniform entity; it's layered, each layer possessing unique characteristics of temperature, pressure, and density. These layers directly influence flight, dictating the altitudes at which different types of aircraft operate most efficiently and safely.

1. Troposphere: The Layer of Weather and Commercial Flight

The troposphere is the lowest layer, extending from the Earth's surface to an average altitude of 7-17 kilometers (4-11 miles), depending on latitude and season. It's where most weather phenomena occur, characterized by decreasing temperature with altitude – a crucial factor for flight planning. Commercial airliners operate primarily within the lower troposphere and occasionally the upper reaches, seeking the most stable and predictable atmospheric conditions. Turbulence, a significant concern for passenger comfort and flight safety, is most prevalent in the troposphere due to the mixing of air masses and convective currents.

- Temperature: Decreases with altitude (average lapse rate of 6.5°C per kilometer).

- Pressure: Decreases significantly with altitude.

- Density: Decreases significantly with altitude. This affects lift generation, requiring higher speeds at higher altitudes to maintain lift.

- Weather: Highly variable; clouds, rain, snow, wind shear, and turbulence are common occurrences.

2. Stratosphere: The Ozone Layer and High-Altitude Flight

Above the troposphere lies the stratosphere, stretching from approximately 17 to 50 kilometers (11 to 31 miles). This layer is characterized by a temperature inversion, meaning the temperature increases with altitude. This is primarily due to the absorption of ultraviolet (UV) radiation by the ozone layer, a critical shield protecting life on Earth from harmful solar radiation. Some high-altitude aircraft, like supersonic jets and weather balloons, venture into the lower stratosphere. However, the lower density of air in this region presents challenges for lift generation and requires specialized aircraft design.

- Temperature: Increases with altitude due to ozone absorption of UV radiation.

- Pressure: Continues to decrease, although less dramatically than in the troposphere.

- Density: Significantly lower than the troposphere, impacting lift and requiring careful flight planning.

- Weather: Relatively calm and stable due to the lack of significant vertical air movement.

3. Mesosphere: Meteors and the Coldest Temperatures

The mesosphere extends from approximately 50 to 85 kilometers (31 to 53 miles). Here, the temperature again decreases with altitude, reaching the coldest temperatures in Earth's atmosphere, around -90°C (-130°F). This layer is sparsely populated by air molecules, and meteors burn up upon entry here, creating shooting stars. No commercial or military aircraft regularly operate in this layer due to the extremely low air density and harsh temperatures.

- Temperature: Decreases with altitude, reaching the coldest temperatures in the atmosphere.

- Pressure: Extremely low.

- Density: Very low; insufficient for aircraft to generate lift.

4. Thermosphere: Auroras and Increasing Temperatures

The thermosphere extends from roughly 85 to 600 kilometers (53 to 372 miles). This layer is characterized by extremely high temperatures, reaching thousands of degrees Celsius, due to the absorption of high-energy solar radiation. However, despite the high temperatures, the air density is so low that the heat isn't directly felt. The International Space Station orbits within the lower thermosphere. Auroras, the spectacular displays of light in the polar skies, occur in the thermosphere due to the interaction of solar particles with atmospheric gases.

- Temperature: Increases dramatically with altitude.

- Pressure: Extremely low.

- Density: Very low, making it unsuitable for conventional aircraft flight.

5. Exosphere: The Fading Boundary

The exosphere is the outermost layer, gradually merging with outer space. There's no clear upper boundary, and air molecules gradually escape into the vacuum of space. Satellites orbit within the exosphere, which is characterized by extremely low density and near-vacuum conditions.

- Temperature: Variable and difficult to define.

- Pressure: Effectively zero.

- Density: Extremely low, essentially a vacuum.

Aircraft Design and Atmospheric Conditions: A Synergistic Relationship

Aircraft design takes into account the specific atmospheric conditions at different altitudes. Commercial airliners, for example, are optimized for operation within the lower troposphere and the lower stratosphere, carefully balancing fuel efficiency with the need for sufficient lift.

High-altitude flight requires specialized designs to account for:

- Lower air density: Larger wings or higher speeds are needed to generate sufficient lift.

- Lower pressure: Aircraft structures need to withstand the significant pressure difference between the cabin and the outside environment.

- Lower temperatures: Materials must be chosen to withstand the extreme cold of the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere.

Low-altitude flight presents different challenges:

- Higher air density: This can lead to increased drag, affecting fuel efficiency.

- Higher turbulence: This poses risks to flight safety and passenger comfort.

- Varied weather conditions: Pilots need to navigate through changes in wind speed, direction, precipitation, and visibility.

Navigating the Atmosphere: Safety and Efficiency

Pilots use sophisticated instruments and technology to monitor and navigate through the different atmospheric layers, ensuring both safety and efficiency. Weather radar helps identify potential hazards like turbulence, thunderstorms, and icing. Air traffic control manages aircraft separation and coordinates flight paths to avoid conflicts.

Atmospheric data is crucial for:

- Flight planning: Determining optimal altitudes and routes.

- Fuel efficiency: Minimizing fuel consumption by flying at altitudes where the atmosphere offers the least resistance.

- Safety: Avoiding potentially hazardous weather conditions.

The Future of Flight: Pushing Atmospheric Boundaries

As technology advances, we may see aircraft venturing into higher altitudes or operating under even more demanding atmospheric conditions. Hypersonic flight, for example, involves speeds significantly exceeding the speed of sound, creating unique aerodynamic and thermal challenges. Understanding the intricacies of the atmosphere is critical to achieving safe and efficient operation in these new realms.

Conclusion: A Symphony of Air and Flight

The Earth's atmosphere is a complex and dynamic system that significantly impacts aviation. From the turbulent troposphere to the rarefied stratosphere, each layer presents unique challenges and opportunities. By understanding these atmospheric conditions and incorporating them into aircraft design and flight planning, we can continue to push the boundaries of aviation safely and efficiently, unlocking the marvels of flight and exploration. The interaction between aircraft design and atmospheric conditions is a continuous dance, a symbiotic relationship where the understanding of one directly influences and improves the other. The atmosphere isn't merely a medium for flight; it's an active participant, shaping the technology and techniques that propel us through the skies.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is The Conservation Of Charge

Mar 19, 2025

-

How Many Faces On A Dice

Mar 19, 2025

-

Which Kingdom Does Not Contain Any Eukaryotes

Mar 19, 2025

-

Database Is A Collection Of Related Data

Mar 19, 2025

-

Is Distilled Water An Acid Or A Base

Mar 19, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Atmosphere Do Planes Fly In . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.