Rusting Of Iron Physical Or Chemical Change

Juapaving

Mar 14, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Rusting of Iron: A Deep Dive into the Chemical Change

Rust, that telltale orange-brown coating on iron and steel, is more than just an aesthetic nuisance. It's a fascinating example of a chemical change, a process that fundamentally alters the material's composition and properties. This article delves into the intricacies of rusting, exploring its underlying chemistry, the factors that influence its rate, and the methods used to prevent this common form of corrosion.

Understanding Rust: A Chemical Perspective

Rust is not a single substance, but rather a complex mixture of hydrated iron(III) oxides, with the most common form being Fe₂O₃·xH₂O. The "x" indicates a variable amount of water molecules incorporated into the structure, which explains the range of colors and textures observed in rust. This formation is the result of a redox reaction, a process involving the transfer of electrons between two species. In the case of rusting, iron loses electrons (oxidation) while oxygen gains them (reduction). This process is significantly accelerated in the presence of water and electrolytes, such as salts.

The Oxidation-Reduction Reaction

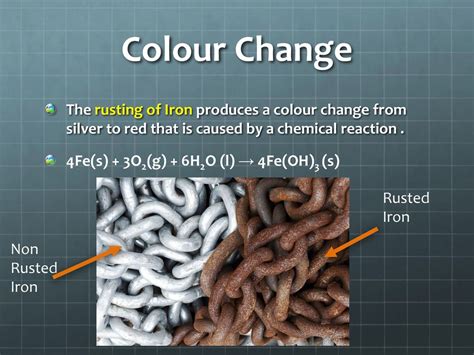

The core chemical reaction behind rusting can be summarized as follows:

4Fe(s) + 3O₂(g) + 6H₂O(l) → 4Fe(OH)₃(s)

This equation shows elemental iron (Fe) reacting with oxygen (O₂) and water (H₂O) to produce iron(III) hydroxide, Fe(OH)₃. This hydroxide then further dehydrates to form various iron oxides and oxyhydroxides, contributing to the complex nature of rust.

2Fe(OH)₃(s) → Fe₂O₃·xH₂O(s) + (3-x)H₂O(l)

The reaction isn't as simple as this overall equation suggests. It involves several intermediate steps and the formation of various iron ions in solution. The overall process is electrochemical in nature, involving anodic and cathodic sites on the iron surface.

Anodic and Cathodic Reactions

The rusting process is not uniform across the iron surface. It involves the formation of anodic and cathodic sites, where oxidation and reduction reactions occur, respectively.

-

Anodic Reaction (Oxidation): At the anodic sites, iron atoms lose electrons and are oxidized to form iron(II) ions:

Fe(s) → Fe²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻

-

Cathodic Reaction (Reduction): At the cathodic sites, oxygen molecules gain electrons and are reduced in the presence of water to form hydroxide ions:

O₂(g) + 2H₂O(l) + 4e⁻ → 4OH⁻(aq)

The electrons released at the anode flow through the iron to the cathode, completing the electrical circuit. The iron(II) ions formed at the anode then react with hydroxide ions at the cathode, eventually forming iron(III) hydroxide, which further dehydrates to form rust.

Fe²⁺(aq) + 2OH⁻(aq) → Fe(OH)₂(s)

4Fe(OH)₂(s) + O₂(g) + 2H₂O(l) → 4Fe(OH)₃(s)

Factors Affecting the Rate of Rusting

Several factors significantly influence the rate at which iron rusts. Understanding these factors is crucial for developing effective rust prevention strategies.

Oxygen Availability

The presence of oxygen is essential for rusting. The higher the concentration of oxygen, the faster the reaction proceeds. This is why iron rusts faster in air than in an oxygen-free environment. Increased air circulation, for instance, will accelerate rusting.

Water Content

Water acts as an electrolyte, facilitating the flow of electrons between the anodic and cathodic sites. The presence of water is crucial for rusting to occur; completely dry iron will not rust. High humidity significantly accelerates the process. The presence of water also increases the concentration of dissolved oxygen.

Acidity (pH)

Acidic conditions accelerate rusting. The presence of acids increases the concentration of H⁺ ions, which can react with the iron and accelerate the oxidation process. Conversely, alkaline conditions (high pH) tend to slow down rusting.

Presence of Electrolytes

Electrolytes, such as salts dissolved in water, increase the conductivity of the solution, enhancing the flow of electrons and accelerating the rusting process. This is why saltwater environments are particularly corrosive to iron. Road salt, for example, significantly accelerates rust formation on vehicles during winter.

Temperature

Higher temperatures generally increase the rate of chemical reactions, including rusting. This is because higher temperatures increase the kinetic energy of the reacting molecules, leading to more frequent and effective collisions.

Surface Area

A larger surface area of iron exposed to the environment will lead to a faster rate of rusting. This is because more sites are available for the oxidation and reduction reactions to occur.

Distinguishing Rusting from Other Changes

It's crucial to understand that rusting is distinctly a chemical change, not a physical one. Physical changes alter the form or appearance of a substance without changing its chemical composition. Examples include melting ice, breaking a glass, or dissolving sugar in water. In contrast, chemical changes alter the chemical composition of a substance, resulting in the formation of new substances with different properties.

Rusting is a chemical change because it involves the formation of new chemical compounds (iron oxides and oxyhydroxides) that have different properties than the original iron. The iron's color changes, its structure is altered, and its properties change; it becomes brittle and flakes off. These are hallmarks of a chemical transformation.

Prevention and Control of Rusting

Preventing or minimizing rust is crucial for protecting iron structures and materials. Various methods are employed for this purpose, including:

Protective Coatings

Applying protective coatings, such as paint, varnish, or galvanization (coating with zinc), creates a barrier between the iron and the environment, preventing oxygen and water from reaching the iron surface.

Cathodic Protection

This method involves connecting the iron object to a more reactive metal, such as zinc or magnesium, which acts as a sacrificial anode. The more reactive metal preferentially corrodes, protecting the iron. This is often used to protect pipelines and underwater structures.

Alloying

Adding other elements to iron, such as chromium and nickel, forms stainless steel, which is significantly more resistant to rusting due to the formation of a protective chromium oxide layer.

Inhibitors

Adding chemical inhibitors to the environment surrounding the iron can slow down the rusting process. These inhibitors interfere with the electrochemical reactions involved in rusting.

Conclusion

Rusting is a complex but fascinating chemical change, crucial to understand for anyone working with iron or steel. The interplay of oxygen, water, acidity, and other factors determines the rate of rusting, emphasizing the need for effective prevention methods. From protective coatings to cathodic protection and alloying, numerous strategies exist to combat this common form of corrosion, extending the lifespan of iron-based materials and preventing significant economic losses. Understanding the underlying chemistry allows for targeted approaches to control and minimize this pervasive chemical reaction. Continued research into innovative materials and preventative techniques is essential for mitigating the challenges posed by rust in our ever-growing industrial and technological landscape.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Lowest Common Multiple Of 9 And 8

Mar 15, 2025

-

Real Life Examples Of Right Angles

Mar 15, 2025

-

What Is Relative Abundance In Chemistry

Mar 15, 2025

-

What Is The Difference Between Ribose And Deoxyribose

Mar 15, 2025

-

What Can 27 Be Divided By

Mar 15, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Rusting Of Iron Physical Or Chemical Change . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.