Orbitals With The Same Energy Are Called

Juapaving

Mar 23, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Orbitals with the Same Energy are Called Degenerate Orbitals: A Deep Dive into Atomic Structure

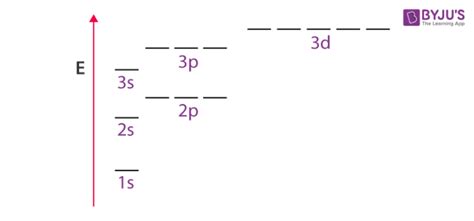

Orbitals are regions of space around an atom's nucleus where there's a high probability of finding an electron. Understanding these orbitals is crucial to grasping the behavior of atoms and molecules. A key concept in this understanding is degeneracy, referring to orbitals possessing the same energy level. This article will explore the concept of degenerate orbitals, examining their causes, consequences, and exceptions, delving into the intricacies of atomic structure and quantum mechanics.

What are Degenerate Orbitals?

Orbitals with the same energy are called degenerate orbitals. This degeneracy arises from the symmetry inherent in the atom's electronic structure. In a hydrogen atom, for instance, the three p orbitals (px, py, and pz) are degenerate, meaning they all possess the same energy level. This is because the hydrogen atom only has one proton and one electron, resulting in a perfectly spherical electron cloud. The absence of electron-electron repulsion simplifies the energy levels.

In simpler terms: Imagine three identical boxes (orbitals) at the same height (energy level). These boxes can hold electrons. Because they're at the same height, an electron can occupy any of them with equal ease – this is degeneracy.

Factors Affecting Orbital Degeneracy

Several factors influence whether orbitals are degenerate:

1. Principal Quantum Number (n)

The principal quantum number (n) determines the energy level of an electron. Orbitals with the same value of 'n' are generally at the same energy level, though this is a simplification that breaks down with increasing complexity of the atom. For a hydrogen atom, all orbitals with the same 'n' are degenerate.

2. Azimuthal Quantum Number (l)

The azimuthal quantum number (l) determines the shape of the orbital (s, p, d, f, etc.). For a given value of 'n', different values of 'l' result in different energy levels. For example, for n=2, the 2s orbital has lower energy than the 2p orbitals. However, within a subshell (defined by 'l'), the orbitals are degenerate.

3. Magnetic Quantum Number (ml)

The magnetic quantum number (ml) specifies the orientation of the orbital in space. For a given 'l', there are 2l + 1 possible values of ml, each corresponding to a different orientation of the orbital. In the absence of an external magnetic field, these orbitals are degenerate. The presence of a magnetic field lifts this degeneracy, causing the energy levels to split (Zeeman effect).

4. Electron-Electron Interactions

In multi-electron atoms, the presence of multiple electrons significantly affects orbital energy. Electron-electron repulsion causes the energies of orbitals within the same subshell to differ slightly. For instance, in a carbon atom, the 2px, 2py, and 2pz orbitals are approximately degenerate, but not perfectly so due to electron-electron interactions. This deviation from perfect degeneracy is a critical difference between hydrogen-like atoms and polyelectronic atoms.

5. External Electric and Magnetic Fields

External fields can disrupt the degeneracy of orbitals. As mentioned earlier, magnetic fields cause the Zeeman effect, while electric fields cause the Stark effect. These effects lead to a splitting of energy levels, removing the degeneracy.

Consequences of Orbital Degeneracy

The degeneracy of orbitals has significant implications for the electronic configuration of atoms and molecules:

-

Electron filling: Electrons fill orbitals according to Hund's rule, which states that electrons will individually occupy each orbital within a subshell before pairing up. This is a direct consequence of degeneracy; electrons preferentially occupy separate, equally energetic orbitals to minimize electron-electron repulsion.

-

Spectroscopy: The degeneracy of orbitals plays a crucial role in atomic spectroscopy. Transitions between degenerate orbitals produce spectral lines that often appear as single peaks, while the lifting of degeneracy (e.g., through the Zeeman effect) can split these peaks into multiple lines, providing valuable information about atomic structure and external fields.

-

Chemical Bonding: The degeneracy and relative energies of orbitals are critical in determining the type and strength of chemical bonds that atoms can form. The overlap of degenerate orbitals of appropriate symmetry can lead to the formation of sigma and pi bonds.

-

Molecular Orbital Theory: In molecular orbital theory, degenerate atomic orbitals combine to form degenerate molecular orbitals, significantly influencing the bonding and electronic properties of molecules.

Exceptions to Degeneracy

While the concept of degeneracy is fundamental, it's important to recognize that it's an idealization that isn't always perfectly realized in real-world systems:

-

Multi-electron atoms: As discussed earlier, electron-electron interactions in multi-electron atoms lead to deviations from perfect degeneracy, making the orbitals within the same subshell only approximately degenerate.

-

External fields: The application of external electric or magnetic fields removes the degeneracy of orbitals, splitting the energy levels and affecting the electronic behavior of the atom or molecule.

-

Relativistic effects: In heavier atoms, relativistic effects become significant, affecting the energies of orbitals and leading to deviations from the non-relativistic predictions of degeneracy. These effects are particularly pronounced for s and p orbitals, which are closer to the nucleus.

Understanding Degeneracy through Examples

Let's illustrate the concept with specific examples:

Hydrogen Atom (n=2):

The hydrogen atom's n=2 energy level has four degenerate orbitals: one 2s orbital and three 2p orbitals (2px, 2py, 2pz). They have the same energy in the absence of external fields.

Carbon Atom (n=2):

In a carbon atom, the n=2 level has 2s and 2p orbitals. While the 2p orbitals (2px, 2py, 2pz) are approximately degenerate, slight differences exist due to electron-electron repulsion and shielding effects. The 2s orbital is at a different, lower energy level.

Lithium Atom (n=2):

Similar to carbon, lithium's n=2 level shows approximate degeneracy in 2p orbitals, but the 2s orbital is at a lower energy. Electron-electron repulsion and shielding cause the deviation from perfect degeneracy.

Advanced Concepts and Further Exploration

The concept of degenerate orbitals opens the door to further exploration of advanced topics in quantum mechanics and atomic physics. These include:

-

Group Theory: Group theory provides a powerful mathematical framework for understanding the symmetry properties of atoms and molecules, including the degeneracy of orbitals.

-

Perturbation Theory: Perturbation theory is a valuable tool for calculating the small energy differences that arise from deviations from perfect degeneracy, such as those caused by electron-electron interactions.

-

Density Functional Theory (DFT): DFT provides a computationally efficient method for calculating the electronic structure of atoms and molecules, taking into account electron correlation effects that affect orbital degeneracy.

Conclusion

Understanding that orbitals with the same energy are called degenerate orbitals is fundamental to grasping atomic structure and the behavior of electrons within atoms and molecules. While the concept of perfect degeneracy is often an idealization, particularly in multi-electron atoms, it remains a critical foundation for understanding more complex phenomena in quantum chemistry and physics. The factors influencing degeneracy, its consequences, and its exceptions highlight the intricate interplay of quantum numbers, electron-electron interactions, and external fields in determining the electronic structure of matter. Continued exploration of this concept is essential for advancements in areas such as material science, spectroscopy, and computational chemistry.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Put Numbers In Order From Least To Greatest

Mar 25, 2025

-

How Many Energy Levels Does Sodium Have

Mar 25, 2025

-

Whats The Difference Between An Alternator And A Generator

Mar 25, 2025

-

Is Air A Compound Or A Mixture

Mar 25, 2025

-

Least Common Multiple Of 16 And 9

Mar 25, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Orbitals With The Same Energy Are Called . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.