Electronic Configuration Of Copper And Chromium

Juapaving

Mar 17, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

The Anomalous Electronic Configurations of Copper and Chromium: A Deep Dive

The periodic table, a seemingly simple arrangement of elements, holds within it a wealth of fascinating chemical behavior. While the Aufbau principle and Hund's rule generally predict the electronic configurations of atoms, exceptions exist that challenge our understanding and highlight the complexities of electron-electron interactions. Two notable exceptions are copper (Cu) and chromium (Cr), whose electronic configurations deviate from the expected pattern, prompting us to explore the underlying reasons for this anomalous behavior. This article delves deep into the electronic configurations of copper and chromium, exploring the principles behind their unique structures and the consequences for their chemical properties.

Understanding Electronic Configuration

Before we delve into the anomalies, let's establish a foundation. An electronic configuration describes the arrangement of electrons within the various energy levels and sublevels of an atom. It follows specific rules:

- Aufbau Principle: Electrons fill orbitals starting from the lowest energy level and progressing upwards.

- Pauli Exclusion Principle: Each orbital can hold a maximum of two electrons, with opposite spins.

- Hund's Rule: Electrons will individually occupy each orbital within a subshell before pairing up.

These rules generally predict the electronic configurations of elements accurately. For example, consider manganese (Mn), with an atomic number of 25. Following the Aufbau principle, its predicted and actual electronic configuration is: 1s²2s²2p⁶3s²3p⁶4s²3d⁵. Each orbital is filled according to the rules, resulting in a stable, half-filled d-subshell.

The Anomaly of Chromium (Cr): A Half-Filled d-Subshell

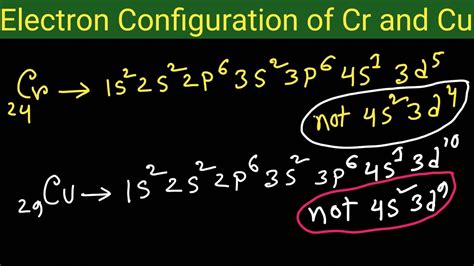

Chromium (Cr), with an atomic number of 24, presents the first anomaly. Based on the Aufbau principle, one might expect its electronic configuration to be 1s²2s²2p⁶3s²3p⁶4s²3d⁴. However, the actual configuration is 1s²2s²2p⁶3s²3p⁶4s¹3d⁵.

Why this deviation? The answer lies in the relative energy levels of the 4s and 3d orbitals. While the 4s orbital is generally lower in energy than the 3d orbital, the energy difference is relatively small. In chromium, the energy gained by having a completely half-filled 3d subshell (with each orbital containing a single electron) outweighs the slight energy difference between the 4s and 3d orbitals. This half-filled configuration provides enhanced stability due to:

- Exchange Energy: Electrons with parallel spins in separate orbitals experience a repulsive force, but this is counteracted by a quantum mechanical effect called exchange energy, which lowers the overall energy of the system. A half-filled d-subshell maximizes exchange energy.

- Symmetrical Electron Distribution: A half-filled d-subshell leads to a more symmetrical electron distribution, further contributing to its stability.

This extra stability associated with the half-filled d-subshell makes the 4s¹3d⁵ configuration more favorable than the predicted 4s²3d⁴ configuration, illustrating the interplay between orbital energies and electron-electron interactions.

Consequences of Chromium's Electronic Configuration

Chromium's unique configuration significantly impacts its chemical properties. The presence of only one electron in the 4s orbital makes it less likely to lose that electron compared to elements with a fully filled 4s subshell. This affects its reactivity and the types of compounds it forms. Chromium exhibits a wide range of oxidation states, reflecting its ability to lose electrons from both the 4s and 3d orbitals.

The Anomaly of Copper (Cu): A Filled d-Subshell

Copper (Cu), with an atomic number of 29, exhibits a similar anomaly. The expected electronic configuration, following the Aufbau principle, is 1s²2s²2p⁶3s²3p⁶4s²3d⁹. However, the actual configuration is 1s²2s²2p⁶3s²3p⁶4s¹3d¹⁰.

Why this deviation? Similar to chromium, the energy difference between the 4s and 3d orbitals is relatively small. In copper's case, the significant energy gain from having a completely filled 3d subshell (with all ten electrons paired) surpasses the energy cost of moving one electron from the 4s orbital to the 3d orbital. A completely filled d-subshell also enjoys enhanced stability due to:

- Increased Exchange Energy (Pairing Energy): While pairing electrons in the same orbital leads to electron-electron repulsion, the stability gain from a filled d-subshell outweighs this cost.

- Shielding Effect: A filled d-subshell effectively shields the outer electrons from the positive nuclear charge, resulting in a more stable configuration.

The fully filled 3d subshell provides exceptional stability, making the 4s¹3d¹⁰ configuration energetically more favorable than the expected 4s²3d⁹ configuration.

Consequences of Copper's Electronic Configuration

The filled d-subshell in copper's configuration profoundly affects its properties. The 4s electron is relatively easily lost, leading to the common +1 oxidation state for copper. However, copper can also exhibit a +2 oxidation state, involving the loss of an electron from the d-subshell. The stability of the fully filled d-subshell influences the relative stability of the +1 and +2 oxidation states, with the +1 state being often preferred in many compounds. The different oxidation states lead to a diverse range of copper compounds with varying colors and properties.

Comparing the Anomalies: Similarities and Differences

Both chromium and copper exhibit anomalous electronic configurations, primarily driven by the relatively small energy difference between the 4s and 3d orbitals. In both cases, the energy gain from achieving a stable, half-filled (Cr) or fully filled (Cu) d-subshell outweighs the energy cost of altering the electron occupancy of the 4s orbital. However, there is a subtle difference:

- Chromium prioritizes half-filled stability: The half-filled 3d subshell in chromium maximizes exchange energy, leading to a more stable configuration.

- Copper prioritizes fully filled stability: The completely filled 3d subshell in copper provides maximum stability through increased exchange energy and improved shielding.

This difference in the driving force behind the anomaly reflects the subtle variations in electron-electron interactions and the delicate balance of energies within the atom.

Implications and Further Exploration

The anomalous configurations of chromium and copper are not mere exceptions; they are crucial for understanding the complex interplay of quantum mechanical principles that govern atomic behavior. These anomalies highlight the limitations of simple models and emphasize the importance of considering electron-electron interactions and the nuances of orbital energy levels when predicting electronic configurations.

Further exploration could involve examining:

- Other transition metals: Investigating whether other transition metals exhibit similar deviations from the Aufbau principle.

- Computational chemistry: Using advanced computational methods to calculate and visualize the energy levels and electron distributions in these atoms.

- Experimental studies: Conducting experiments to further characterize the physical and chemical properties arising from these anomalous configurations.

Conclusion

The anomalous electronic configurations of copper and chromium serve as powerful examples of how the rules governing electronic structure can be subtly modified by the complex interplay of electron-electron interactions and the pursuit of greater stability. While the Aufbau principle provides a useful framework, understanding exceptions like these is critical to grasping the rich complexity of atomic structure and chemical behavior. These anomalies underscore the importance of considering both the energy levels of orbitals and the energetic benefits of half-filled and completely filled subshells in accurately predicting and understanding the properties of elements. By studying these exceptions, we gain a deeper appreciation for the elegance and complexity of quantum mechanics as it applies to the fascinating world of chemistry.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is 25 In A Decimal

Mar 18, 2025

-

The Scattering Of Light By Colloids Is Called

Mar 18, 2025

-

Least Common Multiple Of 2 4 And 8

Mar 18, 2025

-

How Many Equal Sides Does An Isosceles Triangle Have

Mar 18, 2025

-

Full Form Of S I T

Mar 18, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Electronic Configuration Of Copper And Chromium . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.