Which Layer Of Earth Is Hottest

Juapaving

Mar 10, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Which Layer of Earth is Hottest? Delving into the Earth's Fiery Core

The Earth, our vibrant and dynamic planet, is far more than just the surface we inhabit. Beneath our feet lies a complex system of layers, each with its own unique properties and characteristics. One of the most intriguing aspects of this subterranean world is its temperature profile. The question, "Which layer of Earth is hottest?" leads us on a fascinating journey into the planet's fiery heart. While the answer might seem straightforward, understanding why a particular layer is the hottest requires exploring the intricate processes shaping our planet's internal structure and dynamics.

Understanding the Earth's Layered Structure

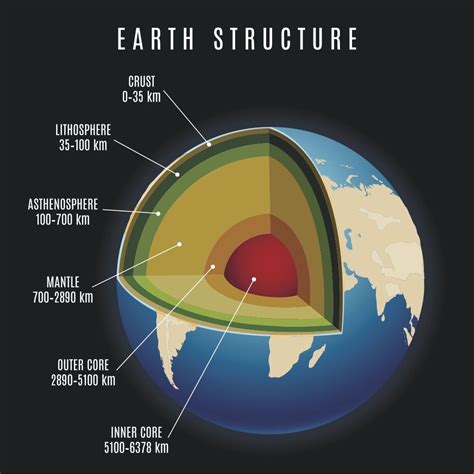

Before diving into the temperature extremes, let's briefly review the Earth's primary layers:

-

Crust: This is the outermost, thinnest layer, composed primarily of solid rock. It's further divided into oceanic crust (thinner and denser) and continental crust (thicker and less dense). The crust's temperature varies significantly, ranging from relatively cool near the surface to increasingly hotter temperatures deeper down.

-

Mantle: The mantle is a much thicker layer beneath the crust, extending to a depth of approximately 2,900 kilometers (1,802 miles). It's composed primarily of silicate rocks rich in iron and magnesium. The mantle is not a uniform solid; rather, it exhibits different rheological properties (how it flows or deforms) with depth, exhibiting both ductile and brittle behavior. The temperatures within the mantle progressively increase with depth.

-

Outer Core: This layer lies beneath the mantle and is approximately 2,200 kilometers (1,367 miles) thick. It's composed primarily of liquid iron and nickel, with smaller amounts of lighter elements. The incredibly high temperatures and pressures in the outer core create the conditions for convection currents, driving the Earth's magnetic field.

-

Inner Core: At the Earth's very center lies the inner core, a solid sphere with a radius of about 1,220 kilometers (758 miles). It's primarily composed of iron and nickel, but the extreme pressure at this depth forces the atoms into a tightly packed, solid state despite the incredibly high temperature.

The Heat Source: Radioactive Decay and Residual Heat

The intense heat within the Earth's interior is primarily generated by two mechanisms:

1. Radioactive Decay:

Radioactive isotopes, such as uranium, thorium, and potassium, are present in the Earth's mantle and crust. As these isotopes decay, they release energy in the form of heat. This radioactive decay process is a continuous source of heat generation, significantly contributing to the overall temperature profile of the planet's interior. The rate of radioactive decay gradually decreases over geological time, but it remains a crucial factor maintaining the Earth's internal heat. This decay is significantly more pronounced in the mantle, leading to considerable heat generation within this layer.

2. Residual Heat:

The Earth formed approximately 4.54 billion years ago through the accretion of dust and gas. This process released a tremendous amount of gravitational energy, which was converted into heat. While a significant portion of this initial heat has been lost over billions of years, a considerable amount remains trapped within the Earth's interior. This residual heat, along with ongoing radioactive decay, fuels the high temperatures observed in the Earth's deeper layers.

Temperature Gradients and the Hottest Layer: The Inner Core

The temperature within the Earth gradually increases with depth, a phenomenon known as the geothermal gradient. However, the rate of temperature increase is not uniform throughout the planet. The inner core is definitively the hottest layer of the Earth, with estimated temperatures ranging from 5200° Celsius (9392° Fahrenheit) to 6000° Celsius (10832° Fahrenheit).

Several factors contribute to the extremely high temperatures in the inner core:

-

Pressure: The immense pressure at the Earth's center compresses the iron and nickel atoms, making them more resistant to thermal expansion. This compression contributes to increased energy density and higher temperatures. The pressure in the inner core is millions of times greater than the pressure at the Earth's surface.

-

Heat Conduction and Convection: Heat from the outer core is conducted and convected into the inner core. This constant influx of heat from the surrounding liquid iron-nickel maintains the inner core’s high temperature. The outer core’s convection currents play a crucial role in transporting heat inwards.

-

Crystallization of the Inner Core: As the liquid iron in the outer core cools and solidifies to form the inner core, a process called crystallization, latent heat is released. This latent heat, along with heat from radioactive decay in the inner core, further elevates the temperature.

Why not the Outer Core?

While the outer core is incredibly hot (estimated temperatures around 4000-5700° Celsius, or 7232-10312° Fahrenheit), it's not as hot as the inner core. The liquid state of the outer core means that heat can be more readily transported through convection currents. These currents efficiently distribute heat throughout the outer core, preventing a massive accumulation of heat in a single point like the inner core. The continuous flow and movement in the outer core help to regulate its temperature.

The Significance of Earth's Internal Heat

The Earth's internal heat is not merely a scientific curiosity; it plays a crucial role in shaping our planet's geology and influencing various processes at the Earth's surface. These processes include:

-

Plate Tectonics: The heat driving mantle convection is the engine of plate tectonics, the process responsible for earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and the formation of mountain ranges. The movement of tectonic plates shapes continents, oceans, and the Earth’s surface features.

-

Volcanism: Volcanic activity is directly linked to the Earth's internal heat. Magma, molten rock generated within the Earth, rises to the surface through volcanic eruptions, releasing heat and gases. Volcanism significantly impacts the atmosphere and contributes to the formation of new crust.

-

Geothermal Energy: Harnessing the Earth's internal heat for energy production is a sustainable alternative energy source. Geothermal power plants utilize heat from underground reservoirs to generate electricity, providing a clean and renewable energy option.

-

Magnetic Field: The convection currents in the Earth's liquid outer core generate the Earth's magnetic field, which shields us from harmful solar radiation. The magnetic field plays a crucial role in protecting life on Earth from the harsh conditions of space.

Conclusion: The Inner Core Remains Supreme

The question of which layer of Earth is hottest unequivocally points to the inner core. Its extreme temperature, a consequence of immense pressure, residual heat, ongoing radioactive decay, and heat transfer from the outer core, makes it the planet's fiery heart. Understanding the complexities of this internal heat generation and transfer allows us to appreciate the dynamic forces shaping our planet and the interconnectedness of the various processes taking place within it. Further research continues to refine our understanding of the Earth's internal structure and the precise temperature ranges within each layer, confirming the inner core’s reign as the Earth's hottest location.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Select The Components Of A Nucleotide

Mar 10, 2025

-

What Are The Common Factors Of 10 And 5

Mar 10, 2025

-

How Are Frequency And Period Related To Each Other

Mar 10, 2025

-

Animal With The Fastest Reaction Time

Mar 10, 2025

-

Is 42 A Prime Or Composite Number

Mar 10, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Which Layer Of Earth Is Hottest . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.