What Units Are Used To Measure Bacteria

Juapaving

Mar 19, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

What Units Are Used to Measure Bacteria?

Measuring bacteria, those microscopic single-celled organisms, requires specialized units due to their incredibly small size. Unlike measuring macroscopic objects with meters or centimeters, bacteria necessitate a different approach, often involving units reflecting their number, mass, or volume. Understanding these units is crucial for researchers, microbiologists, and anyone working with bacterial cultures or samples. This comprehensive guide delves into the various units used to quantify bacteria, explaining their applications and limitations.

Understanding the Challenges of Measuring Bacteria

Before diving into specific units, it's essential to appreciate the inherent difficulties in measuring bacteria. Their minute size, diverse shapes (cocci, bacilli, spirilla), and tendency to form colonies or biofilms present unique challenges. Consequently, we often don't measure individual bacteria directly but instead employ indirect methods to estimate their abundance or biomass.

The Problem of Individual Measurement

Measuring the length, width, and volume of a single bacterium is possible using advanced microscopy techniques like electron microscopy. However, this is time-consuming, and not practical for large-scale analysis. Direct measurements primarily serve research purposes focused on specific bacterial characteristics, not for routine quantification of bacterial populations.

Units for Measuring Bacterial Numbers

The most common approach to measuring bacteria is by quantifying their number. Several units are used for this purpose, each with its specific application.

1. Colony-Forming Units (CFU)

- Definition: CFU represents the number of viable bacteria in a sample capable of forming a colony on a solid growth medium. A single colony theoretically originates from a single bacterial cell.

- Method: A diluted sample is spread on an agar plate and incubated. After incubation, the visible colonies are counted. The number of CFUs is then extrapolated to the original sample concentration.

- Advantages: Relatively simple and inexpensive, applicable to a wide range of bacteria, provides a measure of viable (living) cells.

- Limitations: Assumes that each colony arises from a single cell (which isn't always true, especially with clumping bacteria), susceptible to variations in plating techniques and incubation conditions. It's also an indirect method, measuring colony-forming potential rather than the actual number of individual bacteria.

- Example: A sample might be reported as containing 1 x 10⁶ CFU/ml, meaning one million colony-forming units per milliliter.

2. Cells per Milliliter (cfu/ml or cells/ml)

- Definition: This is a direct count of bacterial cells within a given volume. It can be obtained using direct microscopic counting methods.

- Method: A known volume of bacterial suspension is placed on a counting chamber (e.g., hemocytometer) and the number of cells is counted under a microscope. This technique can also be performed using automated cell counters.

- Advantages: Relatively fast and direct; measures total cells, including both viable and non-viable bacteria.

- Limitations: Can be laborious for high-density samples; requires careful calibration and technique, high concentration of bacteria can cause overlap making the counting process tedious. Small cells can be difficult to resolve, leading to underestimation.

- Example: 5 x 10⁷ cells/ml indicates 50 million bacterial cells per milliliter.

3. Optical Density (OD)

- Definition: OD measures the turbidity or cloudiness of a bacterial suspension. Higher turbidity corresponds to a higher bacterial concentration.

- Method: A spectrophotometer measures the light absorbance or transmission of the bacterial suspension at a specific wavelength (e.g., 600 nm).

- Advantages: Quick and easy, non-destructive, suitable for continuous monitoring of bacterial growth.

- Limitations: Indirect measurement; OD is not directly proportional to cell number, especially at high densities, where light scattering becomes complex. Calibration against a known cell count (e.g., CFU/ml) is often necessary for accurate quantification.

- Example: An OD of 0.5 at 600 nm might correlate with a specific cell concentration after calibration.

Units for Measuring Bacterial Mass

Measuring bacterial mass offers an alternative quantification approach, providing insights into the total biomass present in a sample.

1. Dry Weight

- Definition: The dry weight is the mass of bacteria remaining after the removal of all water content.

- Method: A known volume of bacterial suspension is filtered, dried, and weighed.

- Advantages: Provides a direct measure of biomass, independent of cell size or shape.

- Limitations: Destructive method; time-consuming, results can be affected by the drying method and conditions.

2. Wet Weight

- Definition: The wet weight of a sample indicates the total weight of bacteria and the surrounding liquid medium.

- Method: A bacterial sample collected, and total weight is measured. This is often used for measuring large scale biofilms or bacterial mats.

- Advantages: Less time consuming than the dry weight method.

- Limitations: The wet weight does not accurately reflect the amount of bacterial biomass. It is heavily affected by the amount of water content in the sample.

Units Used in Specialized Bacterial Measurements

Beyond the standard quantification units, various other units are employed for specific measurements relevant to bacterial characteristics:

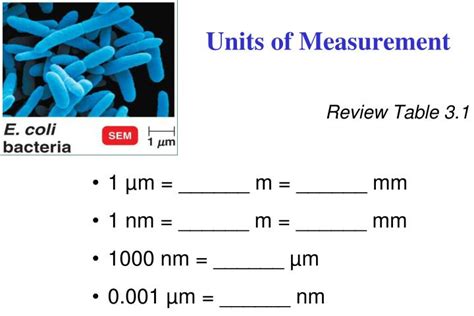

1. Micrometers (µm)

- Definition: A unit of length used to measure the size of individual bacterial cells. One micrometer is one millionth of a meter (10⁻⁶ m).

- Application: Determining bacterial dimensions (length, width, diameter) is critical for identification and characterization.

2. Square Micrometers (µm²)

- Definition: This measures the surface area of bacteria, which relates to nutrient uptake and interaction with the environment.

3. Cubic Micrometers (µm³)

- Definition: This measures the volume of bacteria, crucial for understanding cell growth and metabolic activity.

4. Nanometers (nm)

- Definition: A unit of length used to measure much smaller structures within bacterial cells or on their surfaces (e.g., flagella, pili).

Choosing the Right Unit for Bacterial Measurement

The most suitable unit for measuring bacteria depends entirely on the specific research question or application. The table below summarizes the key considerations:

| Unit | Application | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFU/ml | Measuring viable bacterial count | Simple, inexpensive, measures viability | Indirect, assumptions about colony formation |

| Cells/ml | Measuring total bacterial count | Direct, fast for low density samples | Laborious for high density samples, requires skill |

| OD | Estimating bacterial concentration | Quick, easy, non-destructive | Indirect, requires calibration |

| Dry Weight | Measuring bacterial biomass | Direct, independent of cell size | Destructive, time-consuming |

| Wet Weight | Measuring total mass (bacteria + liquid) | Easier than dry weight | High influence from the water content |

| µm, µm², µm³ | Measuring individual bacterial dimensions | Precise measurement of individual bacterial size | Time-consuming for large scale analysis |

| nm | Measuring sub-cellular structures | Accurate measurement of nanoscale structures | Requires specialized equipment |

Conclusion

Measuring bacteria demands a nuanced approach due to their size and diverse characteristics. Researchers utilize a variety of units to quantify either the number of bacteria (CFU/ml, cells/ml, OD), their mass (dry weight, wet weight), or their dimensions (µm, nm). Selecting the appropriate unit requires careful consideration of the research objective, resources available, and the inherent limitations of each method. Understanding these units and their associated methods is crucial for accurate and meaningful interpretations in microbiology and related fields. Furthermore, continuous developments in microscopy and automated counting techniques are paving the way for more efficient and accurate methods for bacterial quantification, pushing the boundaries of what's possible in understanding the microbial world.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Is Exp The Same As E

Mar 19, 2025

-

Calculate The Molar Mass Of Calcium Nitrate

Mar 19, 2025

-

What Is Study Of Flowers Called

Mar 19, 2025

-

What Is The Complement Of A 45 Degree Angle

Mar 19, 2025

-

What Is The Secondary Structure Of Dna

Mar 19, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Units Are Used To Measure Bacteria . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.