What Is The Smallest Unit Of Matter

Juapaving

Mar 07, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

What is the Smallest Unit of Matter? A Deep Dive into the Quantum Realm

The question, "What is the smallest unit of matter?" has captivated scientists and philosophers for millennia. The answer, however, isn't as straightforward as it might seem. Our understanding of matter has evolved dramatically over time, from ancient Greek atomism to the complex quantum mechanics of today. This journey reveals not only the incredible intricacies of the universe but also the limitations of our current knowledge. This article delves into the fascinating world of subatomic particles, exploring the current scientific consensus and the ongoing debates surrounding the fundamental building blocks of reality.

From Atoms to Subatomic Particles: A Historical Overview

Ancient Greek philosophers, notably Democritus and Leucippus, first proposed the concept of atomos – indivisible particles – as the fundamental constituents of matter. This idea, while conceptually groundbreaking, lacked experimental evidence and remained largely speculative for centuries. It wasn't until the 19th and 20th centuries that scientific advancements provided empirical support for the existence of atoms.

The Atomic Model's Evolution:

-

Dalton's Atomic Theory (Early 1800s): John Dalton revived the atomic concept, proposing that all matter is composed of indivisible atoms, each element having unique atoms with specific mass. This model laid the foundation for modern chemistry.

-

Thomson's Plum Pudding Model (Late 1800s): J.J. Thomson's discovery of the electron shattered Dalton's notion of indivisibility. The plum pudding model depicted the atom as a positively charged sphere with negatively charged electrons embedded within.

-

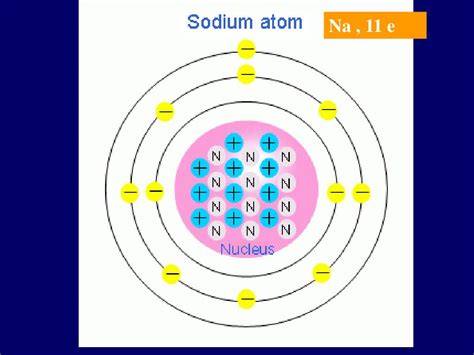

Rutherford's Nuclear Model (Early 1900s): Ernest Rutherford's gold foil experiment revolutionized atomic theory. He discovered that most of an atom's mass and positive charge are concentrated in a tiny nucleus, with electrons orbiting around it.

-

Bohr's Model (1913): Niels Bohr refined Rutherford's model by proposing that electrons orbit the nucleus in specific energy levels, explaining atomic spectra.

-

Quantum Mechanical Model (1920s onwards): The development of quantum mechanics provided a more accurate and sophisticated description of the atom. This model depicts electrons as existing in probability clouds (orbitals) rather than fixed orbits, showcasing the inherent uncertainty in their position and momentum.

Beyond the Atom: Unveiling Subatomic Particles

The quantum mechanical model, while accurate, revealed that atoms themselves are not fundamental. They are composed of even smaller particles:

1. Protons and Neutrons: The Nucleus's Residents

The atom's nucleus contains protons, which carry a positive charge, and neutrons, which are electrically neutral. Both protons and neutrons are composed of even smaller particles called quarks.

2. Electrons: The Orbital Dancers

Electrons, negatively charged particles, occupy the space surrounding the nucleus. Their behavior is governed by the principles of quantum mechanics, making their precise location unpredictable.

3. Quarks: The Fundamental Constituents (So Far)

Currently, quarks are considered fundamental particles. They are elementary particles that cannot be broken down into smaller constituents. There are six types, or "flavors," of quarks: up, down, charm, strange, top, and bottom. Protons and neutrons are each composed of three quarks:

- Proton: Two up quarks and one down quark

- Neutron: One up quark and two down quarks

4. Leptons: The Electron's Family

Electrons belong to a larger family of particles called leptons. Leptons are fundamental particles that do not experience the strong nuclear force (the force that binds quarks together). Besides electrons, other leptons include muons and tau particles, each having its corresponding neutrino.

5. Bosons: The Force Carriers

Unlike fermions (quarks and leptons), which make up matter, bosons mediate the fundamental forces of nature. These include:

- Photons: Carry the electromagnetic force (responsible for light and electromagnetic interactions).

- Gluons: Carry the strong nuclear force (responsible for binding quarks together).

- W and Z bosons: Carry the weak nuclear force (responsible for radioactive decay).

- Gravitons: Hypothetical particles believed to carry the gravitational force. Their existence has yet to be experimentally confirmed.

The Standard Model and Beyond: An Incomplete Picture?

The Standard Model of particle physics is the current theoretical framework that describes the fundamental constituents of matter and their interactions. It successfully explains a vast range of experimental observations but is not a complete theory. Several open questions remain:

- The Hierarchy Problem: Why is the gravitational force so much weaker than the other fundamental forces?

- Dark Matter and Dark Energy: What are these mysterious substances that make up the vast majority of the universe's mass-energy content?

- Neutrino Masses: Why do neutrinos have mass, even though the Standard Model initially predicted they would be massless?

- The Strong CP Problem: Why is the strong force seemingly symmetric under charge conjugation and parity transformations?

String Theory and Beyond: Exploring New Frontiers

Physicists are actively searching for theories that go beyond the Standard Model, addressing these open questions and providing a more complete and unified understanding of the universe. One prominent candidate is string theory, which proposes that fundamental particles are not point-like objects but rather tiny vibrating strings. This approach has the potential to unify all fundamental forces, including gravity, but it lacks experimental verification and remains a highly theoretical framework. Other approaches, such as loop quantum gravity, also attempt to address the limitations of the Standard Model.

Conclusion: The Elusive "Smallest Unit"

The question of the smallest unit of matter remains a compelling scientific puzzle. While quarks are currently considered fundamental constituents, the possibility of even smaller, more fundamental particles remains open. The Standard Model provides a robust framework for understanding the universe at the subatomic level, but it's far from the final word. The ongoing search for a more complete theory drives the frontiers of physics, promising exciting discoveries that will further illuminate the fundamental building blocks of reality and our place within the cosmos. The journey from Democritus' atomos to the complex landscape of quarks, leptons, and bosons exemplifies the enduring human quest to comprehend the universe's intricate mechanisms. The pursuit of knowledge continues, promising further revelations about the smallest units of matter and the mysteries they hold. The answer, at present, is that the smallest unit of matter we know of is a quark, a fundamental particle that comprises protons and neutrons, but the search for deeper understanding relentlessly continues.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Is The Square Root Of 9 A Rational Number

Mar 09, 2025

-

How Many Neutrons Are In Phosphorus

Mar 09, 2025

-

What Is The Percentage Of 3 9

Mar 09, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Is The Smallest Unit Of Matter . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.