What Is The First Event Associated With A Reflex

Juapaving

Mar 16, 2025 · 8 min read

Table of Contents

What is the First Event Associated with a Reflex?

The seemingly simple act of pulling your hand away from a hot stove is far more complex than it appears. This rapid, involuntary response, a reflex, is a cornerstone of our survival mechanisms. Understanding what initiates this process, the very first event associated with a reflex, is crucial to appreciating the intricate workings of our nervous system. It's not just a single event, but a carefully orchestrated sequence, starting with the receptor.

The Receptor: The First Responder

The first event associated with a reflex is the stimulation of a receptor. Receptors are specialized cells or nerve endings that are exquisitely sensitive to specific types of stimuli. In the hot stove example, these are thermoreceptors, specialized sensory neurons located in the skin. These thermoreceptors detect changes in temperature. When your hand encounters the hot stove, the extreme heat triggers these receptors, converting the physical stimulus (heat) into an electrical signal—a process called transduction. This is the absolute starting point of the reflex arc.

Different reflexes involve different types of receptors:

- Mechanoreceptors: These respond to mechanical pressure or deformation, such as touch, pressure, or vibration. Think of the reflex that causes you to withdraw your hand from a sharp object – mechanoreceptors in your skin are the initial sensors.

- Chemoreceptors: These are sensitive to chemical changes, such as taste, smell, or changes in blood pH. The gag reflex, triggered by irritating substances in the mouth, involves chemoreceptors.

- Photoreceptors: These are found in the retina of the eye and respond to light. The pupillary light reflex, where your pupils constrict in bright light, begins with the stimulation of photoreceptors.

- Nociceptors: These are pain receptors, responding to potentially damaging stimuli like extreme heat, cold, or pressure. The hot stove example perfectly illustrates the role of nociceptors.

The intensity of the stimulus directly influences the strength of the receptor potential. A mildly warm surface might trigger only a weak signal, whereas searing heat generates a much stronger signal. This signal strength dictates the magnitude of the subsequent response.

The Receptor Potential: The Initial Signal

The stimulation of the receptor generates a receptor potential, a graded potential. This means the magnitude of the potential is directly proportional to the intensity of the stimulus. Unlike action potentials, which are all-or-none events, receptor potentials can vary in amplitude. A stronger stimulus leads to a larger receptor potential.

If the receptor potential reaches a threshold, it triggers the generation of an action potential. This action potential is the crucial event that propagates the signal along the sensory neuron, initiating the next stage of the reflex arc. The transition from receptor potential to action potential is essential; it ensures the signal is faithfully transmitted across the entire pathway.

The Sensory Neuron: Transmission to the Central Nervous System

The second key player in this initial sequence is the sensory neuron, also known as an afferent neuron. This neuron is directly connected to the receptor. Once the receptor potential reaches the threshold and triggers an action potential in the sensory neuron, the signal is rapidly transmitted towards the central nervous system (CNS) – the brain and spinal cord.

The sensory neuron's axon conducts the action potential via a process of saltatory conduction, if myelinated. This means the action potential "jumps" between the Nodes of Ranvier, the gaps in the myelin sheath, significantly increasing the speed of transmission. This rapid transmission is critical for the speed and effectiveness of reflexes. The faster the signal reaches the CNS, the quicker the response. This is particularly vital in protective reflexes like withdrawing your hand from a hot object – milliseconds matter.

Myelination: Speeding Up the Reflex

The presence of myelin sheaths on sensory neurons dramatically affects the speed of reflex responses. Myelin, a fatty insulating substance, allows for faster propagation of action potentials. The thicker the myelin sheath, the faster the conduction velocity. This explains why reflexes involving myelinated fibers are significantly faster than those involving unmyelinated fibers. The difference can be the margin between a minor burn and a severe injury.

The type of sensory neuron involved also affects the speed. Proprioceptors, sensors that detect muscle stretch and joint position, often have large diameter, heavily myelinated axons, leading to very fast reflexes involved in maintaining balance and coordination.

The Integration Center: Processing the Signal

The sensory neuron transmits the signal to the integration center within the CNS. In many reflexes, particularly simple ones like the withdrawal reflex, this integration center is located in the spinal cord. This bypasses the brain, allowing for an extremely rapid response. This is a crucial aspect of understanding why a reflex is so fast; the signal doesn't need to travel all the way to the brain and back.

Within the integration center, the signal can undergo various processes, including:

- Synaptic Transmission: The signal is transmitted across a synapse, a junction between the sensory neuron and an interneuron or directly to a motor neuron. This involves the release of neurotransmitters, chemical messengers that carry the signal across the synaptic cleft. The type of neurotransmitter released determines whether the signal is excitatory or inhibitory.

- Signal Amplification or Inhibition: The integration center can amplify or inhibit the signal depending on various factors. This allows for fine-tuning of the reflex response and prevents inappropriate or excessive responses.

- Convergence and Divergence: Multiple sensory neurons may converge onto a single interneuron, or a single sensory neuron may diverge onto multiple interneurons or motor neurons. This allows for integration of multiple sensory inputs and coordination of a more complex response.

The Motor Neuron: Initiating the Response

Following processing within the integration center, the signal is transmitted to a motor neuron, also known as an efferent neuron. The motor neuron carries the signal away from the CNS to the effector organ – the muscle or gland that will carry out the reflex response. This is the penultimate step in the reflex arc. The motor neuron's axon extends to the effector organ.

The motor neuron releases neurotransmitters at the neuromuscular junction, the synapse between the motor neuron and the muscle fiber. The neurotransmitter, typically acetylcholine, binds to receptors on the muscle fiber membrane, triggering depolarization and muscle contraction. This contraction produces the observable effect of the reflex, such as withdrawing your hand from the hot stove.

The strength of the muscle contraction is determined by the frequency of action potentials arriving at the neuromuscular junction. Higher frequency leads to a stronger contraction. This allows for graded responses even in simple reflexes.

The Effector Organ: The Observable Response

Finally, we reach the effector organ, the muscle or gland that produces the observable response to the stimulus. In the case of the withdrawal reflex, the effector organ is the bicep muscle in your arm. The contraction of this muscle causes you to pull your hand away from the heat source. The speed and efficiency of this process are testament to the intricate coordination between the various components of the reflex arc.

Other examples of effector organs include glands. The pupillary light reflex involves the iris muscles contracting or relaxing, changing the size of the pupil to regulate light entering the eye. Salivary glands also act as effector organs, producing saliva in response to taste or smell stimuli.

The effector response is often accompanied by a feedback loop. Proprioceptors in the muscles monitor the extent of muscle contraction, providing feedback to the CNS, which adjusts further muscular activity to control movement precision and prevent injury.

Beyond the Simple Reflex Arc: The Complexity of Reflexes

While the basic reflex arc provides a simplified model, actual reflexes are significantly more complex. Many reflexes involve multiple interneurons and pathways, allowing for greater integration and coordination. Feedback mechanisms and adjustments based on experience and context add layers of sophistication to reflex responses. This is particularly evident in postural reflexes, which constantly adjust our posture and balance in response to various sensory inputs.

Furthermore, reflexes are not simply isolated events; they are integrated into broader neural networks, interacting with voluntary movements and higher-level brain functions. Our understanding of reflexes is continually evolving, as researchers unravel the intricacies of neural circuits and the role of reflexes in shaping behavior and maintaining homeostasis.

Clinical Significance: Assessing Reflexes

The assessment of reflexes is a crucial diagnostic tool in neurological examinations. Abnormal reflex responses can indicate damage to the nervous system, such as peripheral neuropathy, spinal cord injuries, or brain lesions. The speed, intensity, and presence or absence of certain reflexes provide valuable clues about the location and nature of neurological impairment.

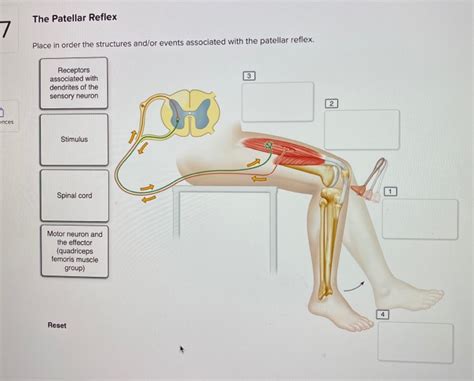

The stretch reflex (knee-jerk reflex) is a classic example of a clinically assessed reflex. Its absence or hyperactivity can indicate specific neurological problems. Other reflexes, such as the plantar reflex (Babinski sign), provide further diagnostic information about the integrity of the nervous system. The careful examination of reflexes aids in diagnosing a range of neurological disorders.

Conclusion: A Coordinated Symphony of Cells

The first event associated with a reflex – the stimulation of a receptor – sets off a chain reaction of events within the nervous system. From the transduction of a physical stimulus into an electrical signal to the coordinated response of muscles or glands, the reflex arc demonstrates the remarkable efficiency and precision of our neural circuits. The intricate interplay between receptors, sensory neurons, integration centers, motor neurons, and effector organs underscores the complexity of even the simplest involuntary responses, highlighting their crucial role in our survival and well-being. Understanding the intricacies of this process is fundamental to appreciating the marvel of the human nervous system.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is The Lcm Of 8 14

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is A Polygon That Has 9 Sides

Mar 17, 2025

-

Why Are Noble Gases Non Reactive

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Is The Lcm Of 9 12

Mar 17, 2025

-

The Atomic Mass Of An Element Is Equal To The

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Is The First Event Associated With A Reflex . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.