What Happens To Acceleration When Mass Is Doubled

Juapaving

Mar 19, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

What Happens to Acceleration When Mass is Doubled? Exploring Newton's Second Law

Understanding the relationship between mass, acceleration, and force is fundamental to classical mechanics. This relationship is elegantly captured by Newton's Second Law of Motion, a cornerstone of physics. This article delves deep into the implications of doubling the mass of an object on its acceleration, exploring the nuances of the equation and providing illustrative examples to solidify your understanding. We'll also consider scenarios where the law might appear to be violated and delve into more complex systems.

Newton's Second Law: The Foundation

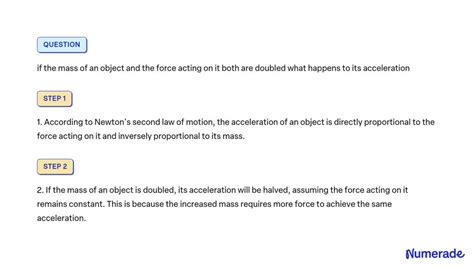

Newton's Second Law states that the acceleration of an object is directly proportional to the net force acting on it and inversely proportional to its mass. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

F = ma

Where:

- F represents the net force acting on the object (measured in Newtons). This is crucial – it's the sum of all forces, considering both magnitude and direction.

- m represents the mass of the object (measured in kilograms). Mass is a measure of an object's inertia – its resistance to changes in motion.

- a represents the acceleration of the object (measured in meters per second squared). Acceleration is the rate of change of velocity.

This simple equation reveals a powerful relationship. Let's dissect it further in the context of our central question: what happens to acceleration when mass is doubled?

Doubling the Mass: Halving the Acceleration

If we assume the net force (F) remains constant, doubling the mass (m) directly impacts the acceleration (a). Let's illustrate this with a simple example:

Imagine a car with a mass of 1000 kg experiencing a net force of 2000 N. Using Newton's Second Law:

a = F/m = 2000 N / 1000 kg = 2 m/s²

Now, let's double the car's mass to 2000 kg, keeping the net force constant at 2000 N. The new acceleration is:

a = F/m = 2000 N / 2000 kg = 1 m/s²

As you can see, doubling the mass while keeping the force constant results in halving the acceleration. This inverse relationship is a direct consequence of Newton's Second Law. The heavier the object, the more resistant it is to changes in its velocity, hence the lower the acceleration for the same applied force.

Visualizing the Relationship

Think of pushing a shopping cart. A nearly empty cart (low mass) accelerates quickly when you push it. However, if you fill the cart with heavy groceries (increased mass), it becomes much harder to accelerate, requiring more force for the same acceleration or resulting in a lower acceleration for the same force.

Constant Acceleration: Doubling the Force

Conversely, if we want to maintain the same acceleration after doubling the mass, we need to double the net force. Let's revisit our car example:

With a mass of 1000 kg and an acceleration of 2 m/s², the required force is 2000 N. If we double the mass to 2000 kg but want to maintain the 2 m/s² acceleration, we need to double the force to 4000 N.

This demonstrates the direct proportionality between force and acceleration when mass is held constant. This is often overlooked when focusing solely on the mass-acceleration relationship. A constant acceleration necessitates a proportional increase in force to compensate for the increased inertia of a larger mass.

Real-World Applications and Considerations

The relationship between mass, force, and acceleration has far-reaching consequences in various real-world scenarios. Consider these examples:

-

Rocket Science: As a rocket burns fuel, its mass decreases. However, the thrust (force) remains relatively constant. Therefore, the rocket's acceleration increases as its mass decreases. This is why rockets accelerate faster as they ascend and burn fuel.

-

Vehicle Design: Car manufacturers carefully consider the mass of a vehicle when designing its engine and braking system. A heavier car needs a more powerful engine to achieve the same acceleration as a lighter car, and more robust brakes to decelerate effectively.

-

Sports: In sports like sprinting or weightlifting, athletes train to optimize their force production while controlling their body mass. Lowering body mass (while maintaining or improving force) leads to increased acceleration, hence better performance.

-

Everyday Actions: Pushing a heavier object requires more effort because you need to apply a greater force to achieve a comparable acceleration.

Beyond the Simple Model: Factors Affecting Acceleration

While Newton's Second Law provides an excellent framework, it's important to acknowledge that real-world situations are rarely this simplistic. Several factors can complicate the relationship between mass and acceleration:

-

Friction: Friction is a force that opposes motion. It depends on the surfaces in contact and the normal force. Increasing mass often increases the friction force, further reducing acceleration. This is why the simple F=ma model may not fully predict real-world behavior in many situations.

-

Air Resistance: Similar to friction, air resistance opposes motion, particularly at higher speeds. The force of air resistance depends on factors like the shape of the object, its velocity, and the density of the air. It increases with velocity, meaning it’s more significant for faster-moving objects and at higher altitudes where the air is less dense.

-

Gravity: Gravity is a significant force affecting the acceleration of objects near the Earth's surface. While often simplified in introductory physics problems, it plays a crucial role in scenarios involving free fall, projectile motion, and inclined planes. The acceleration due to gravity (approximately 9.8 m/s²) is independent of mass, but this only applies to free-falling objects.

Exploring More Complex Systems

Newton's Second Law readily applies to individual objects, but becomes more complex when dealing with systems involving multiple objects or forces. Understanding these complexities requires a deeper understanding of concepts such as:

-

Systems of Particles: In systems with multiple interacting objects, you must consider the net force acting on each object individually.

-

Momentum: Momentum (p = mv) provides a valuable tool for analyzing interactions between objects, particularly collisions. Conservation of momentum principles are frequently used in complex scenarios.

-

Energy: Energy is also crucial, with Kinetic Energy (KE = ½mv²) directly related to the mass and velocity. Understanding energy transfers and transformations can provide further insights into system behavior.

Conclusion: A Fundamental Principle with Nuances

Doubling the mass of an object, while keeping the net force constant, results in halving its acceleration – a direct consequence of Newton's Second Law. This fundamental relationship has far-reaching applications across various fields. However, it’s essential to recognize that real-world scenarios often involve additional forces like friction and air resistance, which complicate the simple model. A deeper understanding of these complexities is necessary for accurate predictions and insightful analysis of real-world systems. Remember that while Newton's Second Law provides a powerful framework, its application necessitates a comprehensive understanding of the system’s dynamics and all forces at play. By combining a solid grasp of this fundamental principle with an appreciation for its nuances, we can approach more advanced concepts in physics and engineering with greater clarity and confidence.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Is Pure Air A Substance Or Mixture

Mar 19, 2025

-

What Is 1 8 In A Percent

Mar 19, 2025

-

Only Moveable Bone In The Skull

Mar 19, 2025

-

Brain Or Heart Which Is More Important

Mar 19, 2025

-

Is Starch A Polymer Of Glucose

Mar 19, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Happens To Acceleration When Mass Is Doubled . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.