The Only Movable Bone In The Skull

Juapaving

Mar 25, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

The Only Movable Bone in the Skull: A Deep Dive into the Mandible

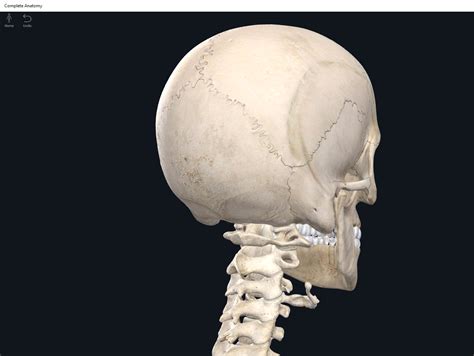

The human skull, a complex and fascinating structure, is largely composed of fused bones, forming a rigid protective casing for the brain. However, amidst this immobility, resides a single exception: the mandible, also known as the jawbone. This remarkable bone is the only movable bone in the skull, playing a pivotal role in vital functions such as chewing, speaking, and facial expression. This article will delve deep into the anatomy, physiology, and clinical significance of this unique and essential skeletal element.

Anatomy of the Mandible: A Closer Look

The mandible, a horseshoe-shaped bone, is the largest and strongest bone in the face. Its intricate structure enables its crucial functionalities. Let's examine its key anatomical features:

Body and Ramus: The Two Main Parts

The mandible is broadly divided into two principal parts: the body and the ramus.

-

Body: The horizontal portion of the mandible forms the lower jawline. It houses the alveolar process, a ridge containing sockets (alveoli) for the lower teeth. The outer surface of the body is marked by the mental protuberance, the chin, and the mental foramina, openings for nerves and blood vessels supplying the chin. The inner surface presents the mylohyoid line, an attachment site for the mylohyoid muscle involved in floor-of-mouth elevation.

-

Ramus: The vertical portion of the mandible, the ramus, ascends from the posterior end of the body. It features two prominent processes: the coronoid process, where the temporalis muscle attaches to elevate the mandible, and the condylar process, which articulates with the temporal bone at the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). The mandibular notch separates these two processes. The posterior border of the ramus is thick and rounded. The medial surface of the ramus possesses the mandibular foramen, which transmits the inferior alveolar nerve and vessels.

Articulation: The Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is where the condylar process of the mandible articulates with the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone. This synovial joint is unique, being a modified hinge joint capable of both hinge and gliding movements, which are crucial for the complex actions of chewing and speaking. The joint is stabilized by ligaments and surrounded by a fibrous capsule. This complex structure makes the TMJ susceptible to a range of disorders, including temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMJD).

Physiology of the Mandible: Movement and Function

The mandible's mobility is not just anatomical; it is a marvel of physiological engineering. Its movement is a finely tuned process involving several muscles, nerves, and blood vessels.

Muscles of Mastication: Powerful Movers

The primary muscles responsible for mandibular movement are the muscles of mastication:

-

Masseter: A powerful muscle located on the side of the jaw, responsible for elevation (closing) of the mandible.

-

Temporalis: A fan-shaped muscle covering the temporal fossa, also contributing to elevation and retraction (backward movement) of the mandible.

-

Medial Pterygoid: A deep muscle that assists in elevation and protraction (forward movement) of the mandible.

-

Lateral Pterygoid: A muscle involved in depression (opening) and protraction of the mandible.

The coordinated actions of these muscles allow for a wide range of mandibular movements, essential for efficient chewing. The precise control of these muscles is also crucial for speech articulation.

Neural Control: Precision and Coordination

Precise control of mandibular movement is achieved through the intricate interplay of cranial nerves. The trigeminal nerve (CN V), specifically its mandibular branch, provides motor innervation to the muscles of mastication. Proprioceptive input from the TMJ and muscles helps regulate the force and direction of mandibular movements, ensuring smooth and coordinated actions.

Vascular Supply: Nourishing the Bone

The mandible receives its blood supply from multiple sources, including the inferior alveolar artery, a branch of the maxillary artery. This artery supplies the teeth and bone of the mandible through its branches. Venous drainage mirrors the arterial supply, with blood returning via corresponding veins.

Clinical Significance: Disorders and Treatments

Given its crucial role in eating, speaking, and facial aesthetics, the mandible is susceptible to various disorders.

Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction (TMJD)

TMJD encompasses a range of conditions affecting the TMJ, causing pain, clicking, locking, and limited jaw movement. Causes range from trauma to arthritis to bruxism (teeth grinding). Treatment may involve conservative approaches like pain relief, physical therapy, or bite guards, or surgical interventions in severe cases.

Fractures: A Common Injury

Mandibular fractures are relatively common injuries, often resulting from trauma to the face. These fractures can range from simple to complex, potentially involving multiple bone fragments. Treatment often involves surgical fixation to stabilize the fractured bone.

Infections: Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis, a serious bone infection, can affect the mandible. This can be caused by bacteria entering through a dental infection or trauma. Prompt diagnosis and treatment with antibiotics are crucial to prevent complications.

Cysts and Tumors: Benign and Malignant

Various cysts and tumors, both benign and malignant, can arise in the mandible. These require appropriate diagnosis and treatment, which may include surgical removal.

Dental Issues: Tooth Loss and Impaction

Dental problems, such as tooth loss and impacted wisdom teeth, can significantly impact the mandible's structure and function. Dental treatment, including extractions or orthodontic correction, may be necessary.

The Mandible in Evolution and Anthropology

The mandible holds significant importance in the field of evolutionary biology and anthropology. Its morphology, including the size, shape, and robusticity, provides valuable insights into the evolutionary history of humans and other primates. Analysis of mandibular features helps researchers understand dietary habits, social structures, and evolutionary adaptations in different hominin populations. The development of the chin, a unique feature of modern humans, is a significant area of study in human evolution.

Conclusion: A Vital Bone

The mandible, the sole movable bone in the skull, is far more than just a structural component. Its intricate anatomy, precise physiological functions, and susceptibility to diverse disorders highlight its crucial role in the human body. Understanding its structure and functionality is essential for professionals in dentistry, surgery, and related fields. Further research into the mandible's biology and evolutionary significance continues to unlock deeper understanding of human anatomy and evolution. This multifaceted bone underscores the intricate beauty and complexity of the human skeletal system. The next time you chew, speak, or smile, take a moment to appreciate the remarkable engineering and vital role of your mandible – the only movable bone in your skull.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Whats The Square Root Of 1

Mar 26, 2025

-

Lcm Of 6 8 And 12

Mar 26, 2025

-

The Minimum Wage Is An Example Of A

Mar 26, 2025

-

Word That Starts With A V

Mar 26, 2025

-

The Red Data Book Keeps A Record Of All The

Mar 26, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about The Only Movable Bone In The Skull . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.