The Movement Of Materials From Low To High Concentration

Juapaving

Mar 26, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

The Movement of Materials from Low to High Concentration: Active Transport and Cellular Life

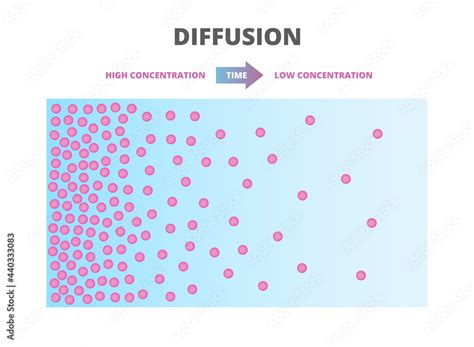

The movement of materials across cell membranes is fundamental to life. While passive transport mechanisms like diffusion and osmosis move substances down their concentration gradients (from high to low concentration), requiring no energy input, many crucial biological processes necessitate the movement of molecules against this gradient – from areas of low concentration to areas of high concentration. This uphill battle against entropy is achieved through active transport, a vital cellular process that consumes energy to ensure cells maintain the proper internal environment for optimal function.

Understanding Concentration Gradients

Before diving into the mechanics of active transport, it's essential to grasp the concept of a concentration gradient. Simply put, this refers to the difference in the concentration of a substance between two areas. Substances naturally tend to move from regions of high concentration to regions of low concentration, a process driven by the inherent tendency of systems to reach equilibrium. This spontaneous movement down the gradient is what powers passive transport.

However, many situations demand the opposite: the accumulation of a specific substance in a particular location even when its concentration is already higher there. This is where active transport steps in, providing the necessary energy to overcome the natural tendency for diffusion.

The Energetic Demands of Active Transport

Active transport is inherently an energy-consuming process. Cells use energy stored in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to power the molecular machinery responsible for moving substances against their concentration gradients. This energy expenditure is necessary to overcome the unfavorable thermodynamic conditions and achieve the desired accumulation of molecules.

This energy is utilized in various ways, depending on the specific active transport mechanism. The key is that active transport directly or indirectly depends on ATP hydrolysis to move substances across the membrane.

Key Mechanisms of Active Transport

Several distinct mechanisms facilitate active transport, each with its unique characteristics and applications within the cell. These include:

1. Primary Active Transport: The ATPase Pumps

Primary active transport directly utilizes the energy released from ATP hydrolysis to drive the movement of molecules. The key players in this process are ATPase pumps, transmembrane proteins that undergo conformational changes upon ATP binding and hydrolysis. This change in shape allows the pump to bind and transport specific molecules across the membrane against their concentration gradient.

One prominent example is the sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+-ATPase), crucial for maintaining the resting membrane potential in animal cells. This pump actively transports three sodium ions (Na+) out of the cell and two potassium ions (K+) into the cell for each ATP molecule hydrolyzed. This creates an electrochemical gradient crucial for nerve impulse transmission, muscle contraction, and numerous other cellular processes.

Other significant primary active transporters include the proton pump (H+-ATPase), which maintains the acidic environment of the stomach and lysosomes, and the calcium pump (Ca2+-ATPase), responsible for regulating intracellular calcium levels – a key messenger in many cellular processes.

2. Secondary Active Transport: Leveraging Existing Gradients

Secondary active transport indirectly uses energy stored in pre-existing concentration gradients established by primary active transport. Instead of directly utilizing ATP, these transporters harness the energy released when another molecule moves down its concentration gradient. This co-transport mechanism often involves two molecules: one moving against its gradient (the transported substance) and the other moving down its gradient (the driving ion).

There are two main subtypes of secondary active transport:

-

Symport: Both molecules move in the same direction across the membrane. A classic example is the sodium-glucose co-transporter (SGLT), which utilizes the sodium ion gradient established by the Na+/K+-ATPase to transport glucose into intestinal epithelial cells.

-

Antiport: The molecules move in opposite directions across the membrane. An example is the sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX), which uses the inward movement of sodium ions to pump calcium ions out of the cell, maintaining low intracellular calcium concentrations.

These secondary active transporters are vital for nutrient uptake, ion regulation, and maintaining cellular homeostasis. They demonstrate the elegant synergy between different active transport mechanisms.

The Importance of Active Transport in Cellular Processes

Active transport is not merely a curious cellular mechanism; it's an indispensable process with far-reaching implications for virtually all aspects of cellular function:

-

Nutrient Uptake: Cells rely on active transport to accumulate essential nutrients, even when their external concentrations are low. This ensures sufficient building blocks for growth and metabolic processes.

-

Ion Homeostasis: Maintaining precise ion concentrations within cells is paramount for cellular function. Active transport mechanisms regulate the levels of crucial ions like sodium, potassium, calcium, and chloride, ensuring optimal cellular environment.

-

Neurotransmission: The sodium-potassium pump is central to the generation and propagation of nerve impulses, underpinning communication within the nervous system.

-

Muscle Contraction: The precise regulation of calcium ions through active transport is critical for muscle contraction and relaxation.

-

Waste Removal: Active transport plays a role in expelling metabolic waste products from cells, preventing their toxic accumulation.

Active Transport and Disease

Dysfunctions in active transport mechanisms can lead to various pathological conditions. For instance, mutations affecting the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein, which is involved in chloride ion transport, cause cystic fibrosis, a debilitating genetic disease. Similarly, defects in the sodium-potassium pump can contribute to cardiac arrhythmias and other cardiovascular problems.

Studying Active Transport: Techniques and Approaches

Understanding the intricacies of active transport requires sophisticated experimental approaches. Techniques used to investigate active transport include:

-

Patch clamping: This technique allows researchers to measure the electrical currents associated with ion transport across individual ion channels.

-

Fluorescence microscopy: Fluorescently labeled molecules can be used to track the movement of substances across cell membranes.

-

Molecular biology techniques: These methods, such as site-directed mutagenesis, allow scientists to alter specific amino acids in transporter proteins to explore their functional roles.

Future Directions in Active Transport Research

Ongoing research continues to unravel the complex details of active transport mechanisms. Areas of ongoing investigation include:

-

Structure-function relationships: Determining the three-dimensional structures of active transporters to better understand their function at the molecular level.

-

Regulation of active transport: Investigating the factors that control the activity of transporters in response to various stimuli.

-

Therapeutic applications: Exploring the potential of manipulating active transport for the treatment of various diseases.

Conclusion

Active transport stands as a testament to the ingenuity and complexity of cellular life. This remarkable process, which moves substances against their concentration gradients, is fundamental to cellular function, enabling nutrient uptake, ion regulation, and numerous other essential processes. Further investigation into this crucial biological mechanism promises to yield valuable insights into cellular health and disease, paving the way for novel therapeutic strategies. Understanding the energetic demands and diverse mechanisms of active transport highlights the intricate orchestration of life at the cellular level, constantly working to maintain balance and function despite the natural tendency towards disorder. The constant interplay between active and passive transport ensures cells maintain the precise internal environment required for survival and function, highlighting the beautiful complexity of biological systems.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How Much Cerebral Capacity Do Dolphins Use

Mar 29, 2025

-

The Original Three Components Of The Cell Theory Are That

Mar 29, 2025

-

Give The Temperature And Pressure At Stp

Mar 29, 2025

-

Give The Ground State Electron Configuration For Pb

Mar 29, 2025

-

Worksheet On Simple Compound And Complex Sentences With Answers

Mar 29, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about The Movement Of Materials From Low To High Concentration . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.