Non Superimposable Mirror Images Are Called

Juapaving

Mar 24, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

Non-Superimposable Mirror Images: A Deep Dive into Chirality

Non-superimposable mirror images are a fascinating concept in chemistry and beyond, with implications spanning from pharmaceuticals to the origins of life. These images, also known as enantiomers or optical isomers, are crucial to understanding molecular structure and its impact on various properties and functions. This article delves into the intricacies of chirality, exploring its definition, causes, detection methods, and significant applications across diverse scientific fields.

Understanding Chirality: The Handedness of Molecules

Chirality, derived from the Greek word "cheir" meaning hand, refers to the property of a molecule that makes it non-superimposable on its mirror image. Think of your left and right hands: they are mirror images of each other, but you cannot overlay them perfectly. This is analogous to chiral molecules. Molecules possessing this property are said to be chiral, while those that are superimposable on their mirror images are achiral.

The Key Role of Asymmetric Carbon Atoms

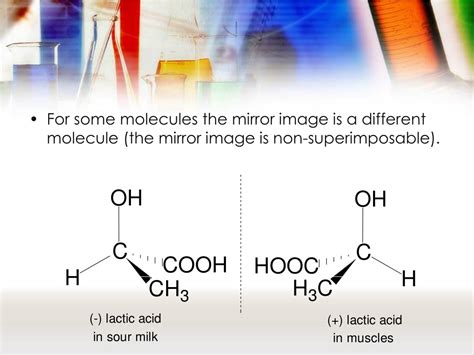

Chirality often arises due to the presence of an asymmetric carbon atom, also known as a chiral center or stereocenter. This is a carbon atom bonded to four different groups. The different arrangements of these groups around the carbon atom lead to the formation of two non-superimposable mirror images.

Example: Consider a molecule with a carbon atom bonded to a hydrogen atom, a methyl group (CH3), a hydroxyl group (OH), and a carboxyl group (COOH). Two different spatial arrangements of these groups around the carbon atom are possible, resulting in two enantiomers. These are often denoted as (R)- and (S)-enantiomers using the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog (CIP) priority rules.

Beyond Asymmetric Carbons: Other Sources of Chirality

While asymmetric carbon atoms are the most common source of chirality, it's crucial to note that other structural features can also lead to non-superimposable mirror images. These include:

- Axial Chirality: Present in molecules with a chiral axis, where rotation around that axis creates a non-superimposable mirror image. Allenes (molecules with two adjacent double bonds) are a prime example.

- Planar Chirality: Observed in molecules with a chiral plane, where the molecule is not superimposable on its reflection. Certain substituted biphenyls exhibit this type of chirality.

- Helical Chirality: This type of chirality arises from the helical arrangement of atoms in a molecule, like in certain proteins or DNA.

Distinguishing Enantiomers: Techniques and Methods

Identifying and distinguishing between enantiomers requires specialized techniques, as their physical and chemical properties are largely identical in achiral environments. However, they interact differently with plane-polarized light and in chiral environments.

Optical Activity: The Polarimeter's Role

The most characteristic difference between enantiomers lies in their interaction with plane-polarized light. A polarimeter measures this interaction, known as optical activity. Enantiomers rotate plane-polarized light in opposite directions; one rotates it clockwise (+ or d-isomer), while the other rotates it counter-clockwise (- or l-isomer). The magnitude of rotation is called specific rotation and is a characteristic property of each enantiomer.

Chiral Chromatography: Separating the Enantiomers

Separating enantiomers is a significant challenge due to their similar properties. Chiral chromatography offers a powerful solution. This technique uses chiral stationary phases in chromatography columns that interact differently with each enantiomer, leading to their separation. Various types of chiral stationary phases exist, based on different principles of enantiomer recognition.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: A Powerful Tool

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy, particularly when using chiral shift reagents, can provide valuable information for distinguishing enantiomers. These reagents form diastereomeric complexes with the enantiomers, leading to distinguishable NMR signals.

The Significance of Chirality in Various Fields

The impact of chirality extends far beyond the realm of theoretical chemistry. It plays a vital role in numerous fields, influencing the properties and behavior of molecules and impacting various biological processes.

Pharmaceuticals: A Tale of Two Enantiomers

The pharmaceutical industry is arguably the field most profoundly affected by chirality. Often, only one enantiomer of a chiral drug is responsible for the desired therapeutic effect, while the other may be inactive or even harmful. For instance, one enantiomer of thalidomide possessed sedative properties, while the other caused severe birth defects. This tragic case highlighted the crucial importance of chiral purity in drug development. Modern drug development emphasizes the synthesis and use of single enantiomers to maximize efficacy and minimize side effects.

Biology and Biochemistry: The Chirality of Life

Life itself is fundamentally chiral. Amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, are predominantly L-enantiomers, while sugars are mostly D-enantiomers. This homochirality is a remarkable feature of life, though its origins remain a subject of ongoing research. The preference for one enantiomer over another in biological systems stems from the chiral nature of enzymes and receptors, which interact selectively with specific enantiomers.

Materials Science: Chirality in Advanced Materials

Chirality is also impacting the development of advanced materials. Chiral molecules can self-assemble into chiral structures, leading to materials with unique optical, electrical, and mechanical properties. These properties find applications in areas such as liquid crystals, sensors, and catalysts.

Food Science and Flavor: The Chiral World of Taste

Enantiomers can exhibit vastly different tastes and aromas. For example, one enantiomer of carvone smells like spearmint, while the other smells like caraway. This difference arises from the specific interactions between the chiral molecules and chiral receptors in the olfactory system.

Future Directions and Research

Research on chirality continues to advance rapidly, driving innovation across numerous fields. The development of more efficient methods for enantiomer separation, synthesis of specific enantiomers, and understanding the origins of biomolecular homochirality are key areas of active investigation. Furthermore, the exploration of the unique properties of chiral materials and their potential applications in various technologies promises exciting breakthroughs in the years to come.

Conclusion

Non-superimposable mirror images, also known as enantiomers, are a fundamental concept in chemistry with far-reaching consequences. Understanding chirality is crucial in diverse fields, including pharmaceuticals, biology, materials science, and food science. The continued exploration of chiral molecules and their properties will undoubtedly drive innovation and lead to exciting discoveries in the future, paving the way for new materials, drugs, and technologies. The handedness of molecules—a seemingly subtle difference—holds immense power in shaping our world.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Can An Even Number Be A Prime Number

Mar 25, 2025

-

What Are The Factors Of 112

Mar 25, 2025

-

What Is The Lowest Common Multiple Of 3 And 8

Mar 25, 2025

-

How Many Centimeters Is 20 Inches

Mar 25, 2025

-

Why Is The Earth Called A Blue Planet

Mar 25, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Non Superimposable Mirror Images Are Called . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.