Moment Of Inertia For A Solid Sphere

Juapaving

Mar 18, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Moment of Inertia for a Solid Sphere: A Comprehensive Guide

The moment of inertia, a crucial concept in physics and engineering, quantifies an object's resistance to changes in its rotation. Understanding this property is essential for analyzing rotating systems, from simple spinning tops to complex machinery. This comprehensive guide delves into the calculation and significance of the moment of inertia for a solid sphere, exploring various approaches and applications.

What is Moment of Inertia?

Before diving into the specifics of a solid sphere, let's establish a firm understanding of the fundamental concept of moment of inertia (often denoted as I). It's the rotational equivalent of mass in linear motion. While mass resists changes in linear velocity, moment of inertia resists changes in angular velocity. The greater the moment of inertia, the more difficult it is to start, stop, or change the rotational speed of an object.

Mathematically, the moment of inertia is defined as the sum of the products of each particle's mass and the square of its distance from the axis of rotation. For a continuous body like a solid sphere, this sum becomes an integral:

I = ∫ r² dm

where:

- I is the moment of inertia

- r is the perpendicular distance of a mass element dm from the axis of rotation

- dm is an infinitesimally small mass element

The value of I depends not only on the object's mass but also on its mass distribution relative to the axis of rotation. A solid sphere's moment of inertia will differ depending on whether the axis of rotation passes through its center or elsewhere.

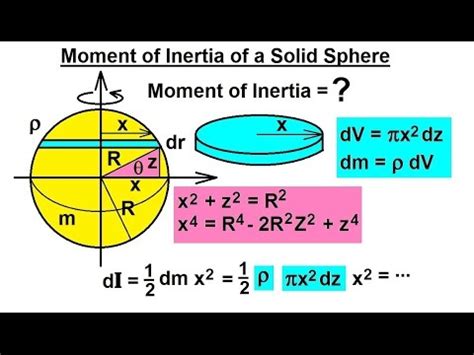

Calculating the Moment of Inertia for a Solid Sphere

Calculating the moment of inertia for a solid sphere involves a triple integral, considering the spherical coordinates system. Let's break down the process step-by-step:

1. Defining the Mass Element:

We consider a small mass element dm within the sphere. The density (ρ) of the sphere is assumed to be uniform throughout. Therefore, the mass of this small element is given by:

dm = ρ dV

where:

- ρ is the density of the sphere (mass/volume)

- dV is the volume of the small mass element

2. Expressing dV in Spherical Coordinates:

In spherical coordinates, the volume element dV is expressed as:

dV = r² sin θ dr dθ dφ

where:

- r is the radial distance from the center of the sphere

- θ is the polar angle (measured from the positive z-axis)

- φ is the azimuthal angle (measured from the positive x-axis)

3. Setting up the Triple Integral:

Substituting the expressions for dm and dV into the moment of inertia equation, we obtain:

I = ∫∫∫ ρ r⁴ sin θ dr dθ dφ

The limits of integration are:

- r: 0 to R (where R is the radius of the sphere)

- θ: 0 to π

- φ: 0 to 2π

4. Solving the Triple Integral:

Solving this triple integral involves integrating with respect to r, θ, and φ sequentially. The density ρ is a constant and can be taken outside the integral. The integration proceeds as follows:

I = ρ ∫₀²π ∫₀π ∫₀ᴿ r⁴ sin θ dr dθ dφ

This integral evaluates to:

I = (2/5) M R²

where:

- M is the total mass of the sphere (M = (4/3)πR³ρ)

- R is the radius of the sphere

Therefore, the moment of inertia of a solid sphere about an axis passing through its center is (2/5)MR².

Understanding the (2/5)MR² Result

The result (2/5)MR² reveals several key insights:

-

Dependence on Mass: The moment of inertia is directly proportional to the mass of the sphere. A more massive sphere will have a greater resistance to rotational changes.

-

Dependence on Radius: The moment of inertia is proportional to the square of the radius. A larger sphere will have a significantly greater moment of inertia, even if its mass is the same as a smaller sphere. This is because a larger fraction of the mass is located farther from the axis of rotation.

-

Constant of Proportionality: The constant (2/5) reflects the specific mass distribution within a solid sphere. This constant will differ for other shapes. For example, a solid cylinder has a moment of inertia of (1/2)MR², and a thin hoop has a moment of inertia of MR².

Moment of Inertia for Different Rotation Axes

The moment of inertia calculated above is specifically for an axis passing through the center of the sphere. If the axis of rotation is different, the calculation becomes more complex. The parallel axis theorem provides a way to calculate the moment of inertia about a parallel axis if the moment of inertia about the center of mass is known:

I = Icm + Md²

where:

- I is the moment of inertia about the new axis

- Icm is the moment of inertia about the center of mass

- M is the mass of the sphere

- d is the distance between the two parallel axes

Applications of Moment of Inertia for a Solid Sphere

The moment of inertia of a solid sphere finds extensive applications in various fields:

1. Astronomy: Understanding the moment of inertia of planets and stars is crucial for analyzing their rotation, gravitational interactions, and overall dynamics.

2. Engineering: The concept is paramount in designing rotating machinery, such as flywheels, gyroscopes, and various types of motors and turbines.

3. Physics: The moment of inertia plays a vital role in understanding angular momentum, rotational kinetic energy, and the precession of rotating objects.

4. Sports Science: Analyzing the motion of sports equipment like bowling balls or spherical projectiles utilizes the moment of inertia calculations for accurate trajectory prediction.

5. Robotics: Designing and controlling robots with spherical joints relies heavily on understanding the moment of inertia to predict and control their movement.

Advanced Concepts and Considerations

While the (2/5)MR² formula is accurate for a perfectly uniform solid sphere, real-world objects might deviate slightly. In such cases, more sophisticated techniques might be required, considering non-uniform density or irregular shapes. Numerical methods, like finite element analysis, can be employed to determine the moment of inertia for complex objects.

Furthermore, the moment of inertia tensor, a 3x3 matrix, provides a more comprehensive description of an object's rotational inertia, particularly for irregularly shaped bodies.

Conclusion

The moment of inertia for a solid sphere, (2/5)MR², is a fundamental concept with broad applications. Understanding its derivation, significance, and application across various fields underscores its importance in both theoretical physics and practical engineering. Whether analyzing planetary rotation or designing high-performance machinery, this seemingly simple formula forms the bedrock of many complex calculations and engineering designs. By grasping the principles discussed in this guide, one can effectively utilize this crucial concept in numerous scientific and engineering endeavors. Further exploration into advanced concepts and the moment of inertia tensor can unlock even deeper understanding of rotational dynamics and complex systems.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Are The Multiples Of Eight

Mar 18, 2025

-

Which Element Does Not Contain Any Neutrons

Mar 18, 2025

-

What Is One Fifth As A Percentage

Mar 18, 2025

-

Which Is Greater 2 5 Or 1 3

Mar 18, 2025

-

Least Common Multiple Of 10 And 7

Mar 18, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Moment Of Inertia For A Solid Sphere . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.