Is Rusting Of Iron A Chemical Change

Juapaving

Mar 20, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Is Rusting of Iron a Chemical Change? A Deep Dive into Oxidation

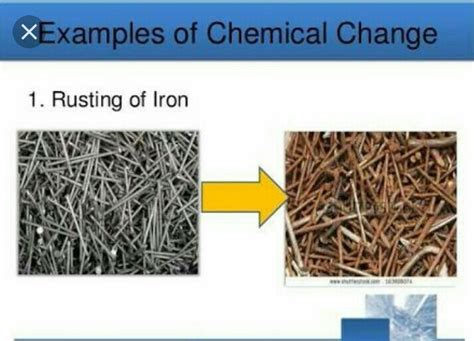

Rusting, that familiar orange-brown coating on iron and steel, is more than just an aesthetic nuisance. It's a fascinating chemical process that fundamentally alters the material's properties. This comprehensive article delves into the science behind rust formation, definitively establishing it as a chemical change and exploring its implications.

Understanding Chemical Changes

Before we dissect the rusting process, let's establish a clear understanding of what constitutes a chemical change. A chemical change, also known as a chemical reaction, involves the transformation of one or more substances into entirely new substances with different chemical properties. These changes are often irreversible, and they involve the breaking and forming of chemical bonds. Key indicators of a chemical change include:

- Formation of a new substance: The product(s) have different physical and chemical properties than the reactants.

- Change in color: A noticeable shift in hue often signals a chemical reaction.

- Release or absorption of heat: Exothermic reactions release heat, while endothermic reactions absorb it.

- Production of gas: The formation of bubbles or fumes is a strong indicator.

- Formation of a precipitate: The appearance of a solid from a solution.

The Chemistry of Rust: A Detailed Examination

Rust, chemically known as iron(III) oxide (Fe₂O₃), isn't simply iron with a coat of paint. It's a completely different compound with distinct properties. The formation of rust is a complex process, primarily driven by oxidation, a chemical reaction involving the loss of electrons. Let's break down the intricate steps:

1. Oxidation: The Loss of Electrons

At the heart of rusting lies the oxidation of iron. Iron atoms readily lose electrons, transforming from neutral Fe atoms to Fe²⁺ ions (ferrous ions) or Fe³⁺ ions (ferric ions). This electron loss is facilitated by the presence of an oxidizing agent, typically oxygen (O₂) from the air.

2. Reduction: The Gain of Electrons

Simultaneously, the oxygen molecules gain electrons, undergoing reduction. This reduction process transforms oxygen molecules into oxide ions (O²⁻).

3. The Role of Water and Electrolytes

While oxygen is the primary oxidizing agent, water plays a crucial role in facilitating the rusting process. Water acts as a medium for the movement of ions, effectively connecting the areas where oxidation and reduction occur. The presence of electrolytes, such as salts dissolved in water, significantly accelerates the process by increasing the conductivity of the solution. This explains why rusting is faster in salty environments, like coastal regions.

4. The Formation of Iron Oxide Hydrates

The iron ions (Fe²⁺ or Fe³⁺) and oxide ions (O²⁻) then combine with water molecules (H₂O) to form various iron oxide hydrates. These hydrates are responsible for the characteristic orange-brown color of rust. The exact composition of rust can vary depending on the environmental conditions.

5. Electrochemical Process: Analogy to a Battery

Rust formation can be viewed as a miniature electrochemical cell. Different areas on the iron surface act as anodes (where oxidation occurs) and cathodes (where reduction occurs). Electrons flow from the anode (iron) to the cathode (often another part of the iron surface), creating an electric current. This electrochemical process continuously drives the oxidation of iron and the formation of rust.

Irreversible Nature: The Hallmark of a Chemical Change

One of the most compelling arguments for classifying rusting as a chemical change is its irreversible nature. Simply removing the rust from the iron surface doesn't revert the iron back to its original state. The iron atoms have undergone a fundamental transformation, forming new chemical bonds within the iron oxide structure. This is unlike physical changes, such as melting ice, where the water molecules remain unchanged in their chemical composition.

Evidence Supporting Chemical Change: Beyond Observation

Beyond the observable changes in color and texture, several pieces of evidence firmly establish rusting as a chemical change:

- Change in mass: The rusted iron will weigh more than the original iron due to the addition of oxygen and water molecules.

- Different chemical properties: Rust is far less reactive than pure iron. It doesn't conduct electricity as well and has a significantly different melting point.

- Heat generation: While not always readily noticeable, the rusting process is mildly exothermic, releasing a small amount of heat.

- Inability to reverse the process easily: While methods exist to remove rust, the process of restoring the iron to its pristine state is complex and generally requires chemical interventions. It's not simply a matter of cleaning or scraping.

Factors Affecting the Rate of Rusting

Several factors significantly influence the rate at which iron rusts:

- Exposure to oxygen: Increased oxygen levels accelerate rusting.

- Exposure to water: The presence of water, particularly in the form of moisture or humidity, is crucial for the process.

- Temperature: Higher temperatures generally speed up the reaction rate.

- Acidity (pH): Acidic environments significantly accelerate rusting.

- Presence of electrolytes: As mentioned earlier, salts and other electrolytes increase conductivity, dramatically increasing the rate of rust formation.

- Surface area: A larger surface area of iron exposed to the environment leads to faster rusting.

Protecting Against Rust: Practical Applications

Understanding the chemistry of rust is crucial for developing effective strategies to prevent or minimize its formation. Common methods include:

- Coatings: Applying protective coatings like paint, varnish, or zinc (galvanization) creates a barrier between the iron and the environment.

- Alloying: Creating alloys, such as stainless steel, incorporates elements like chromium that form a protective oxide layer, preventing further oxidation.

- Inhibitors: Adding corrosion inhibitors to the environment can slow down the rusting process.

- Cathodic protection: Using a sacrificial anode, such as zinc, to protect the iron structure by preferentially oxidizing.

Conclusion: Rusting as a Definitive Chemical Change

In conclusion, the evidence overwhelmingly supports the classification of rusting as a chemical change. The formation of iron(III) oxide (Fe₂O₃) involves a fundamental transformation of iron, creating a new substance with vastly different properties. The irreversible nature of the process, coupled with the changes in mass, chemical properties, and the involvement of electron transfer, unequivocally points to a chemical reaction. Understanding this chemical process is vital for developing effective strategies to combat rust and protect iron-based materials from its detrimental effects. The intricate details of rust formation showcase the power and elegance of chemistry in our everyday world. From the microscopic level of electron transfer to the macroscopic manifestation of orange-brown corrosion, rusting serves as a powerful example of the transformative nature of chemical reactions. The continued research into rust prevention and mitigation highlights the ongoing relevance and importance of understanding this ubiquitous chemical process.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Percent Of 150 Is 25

Mar 21, 2025

-

What Color Has The Longest Wavelength

Mar 21, 2025

-

5 Out Of 8 As A Percentage

Mar 21, 2025

-

Boiling Point Of Water Kelvin Scale

Mar 21, 2025

-

150 Cm Is How Many Inches

Mar 21, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Is Rusting Of Iron A Chemical Change . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.