Digestion Of Food Is Chemical Or Physical Change

Juapaving

Mar 15, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

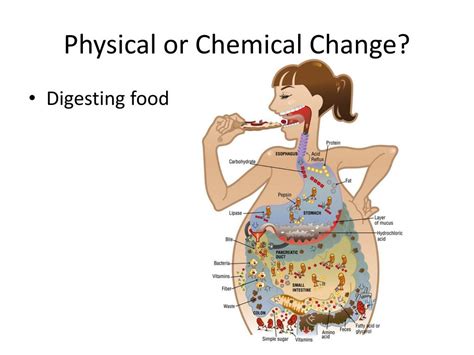

Is Food Digestion a Chemical or Physical Change? A Deep Dive

The process of digestion, the breakdown of food into absorbable nutrients, is often simplified as a single process. However, a closer look reveals a complex interplay of both chemical and physical changes, working in concert to transform your meal into usable energy. Understanding this duality is key to appreciating the intricate machinery of your digestive system. This article explores the physical and chemical aspects of digestion, examining the roles of various organs and highlighting the crucial difference between these two types of changes.

The Physical Aspect of Digestion: Mechanical Breakdown

The physical aspect of digestion, often termed mechanical digestion, involves the physical breakdown of food into smaller pieces. This process increases the surface area of the food, making it more accessible to the enzymes involved in chemical digestion. Several key players contribute to this essential phase:

1. Mastication (Chewing): The First Step

The journey begins in the mouth. Mastication, or chewing, uses your teeth to physically break down food into smaller particles. This initial grinding action significantly increases the surface area available for enzymatic action later in the digestive tract. The saliva produced by the salivary glands not only lubricates the food but also begins the chemical process with the enzyme amylase.

2. Peristalsis: The Muscular Movement

Once swallowed, food enters the esophagus and is propelled down toward the stomach via peristalsis. This involuntary wave-like muscular contraction pushes the food bolus (the chewed mass) through the digestive tract. The rhythmic contractions are crucial for moving the food along, preventing reflux and ensuring efficient mixing with digestive juices. This mechanical action continues throughout the stomach and intestines.

3. Churning in the Stomach: The Mixing Bowl

The stomach serves as a mixing chamber. Its muscular walls contract powerfully, churning and mixing the food with gastric juices. This creates a semi-liquid mixture called chyme. The churning action further breaks down food particles, exposing them to the chemical digestive enzymes. The pyloric sphincter then regulates the release of chyme into the small intestine in controlled amounts.

4. Segmentation in the Small Intestine: Maximizing Absorption

In the small intestine, a different type of muscular contraction called segmentation occurs. This involves rhythmic contractions that divide and mix the chyme, promoting contact between the chyme and the intestinal wall for optimal nutrient absorption. The villi and microvilli, tiny finger-like projections lining the small intestine, further enhance the surface area for absorption.

The Chemical Aspect of Digestion: Enzymatic Breakdown

While physical digestion prepares the food for absorption, chemical digestion is where the actual breakdown of complex food molecules into smaller, absorbable units takes place. This process relies heavily on enzymes, biological catalysts that accelerate chemical reactions.

1. Saliva's Role: Initial Carbohydrate Digestion

The first chemical digestion begins in the mouth with saliva. Salivary amylase, an enzyme in saliva, starts the breakdown of complex carbohydrates like starch into simpler sugars, initiating the process of carbohydrate digestion.

2. Stomach Acid: Protein Denaturation

In the stomach, the highly acidic environment (pH 1.5-3.5) plays a crucial role. The strong hydrochloric acid (HCl) denatures proteins, unfolding their complex three-dimensional structures. This denaturation makes the proteins more susceptible to the action of pepsin, an enzyme that begins the digestion of proteins. HCl also kills many harmful bacteria ingested with food.

3. Pancreatic Enzymes: The Powerhouse of Digestion

The pancreas, a vital digestive organ, releases a cocktail of enzymes into the small intestine. These enzymes include:

- Pancreatic amylase: Continues the breakdown of carbohydrates.

- Trypsin and chymotrypsin: Break down proteins into smaller peptides.

- Lipase: Breaks down fats (lipids) into fatty acids and glycerol.

These enzymes are crucial for completing the breakdown of proteins, carbohydrates and lipids.

4. Intestinal Enzymes: The Finishing Touches

The small intestine itself produces additional enzymes, such as peptidases and sucrase, that further break down peptides into amino acids and disaccharides into monosaccharides respectively. These enzymes ensure the final stages of digestion are completed before absorption.

5. Bile: Emulsification of Fats

Bile, produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder, isn't an enzyme. However, it plays a vital role in fat digestion through a process called emulsification. Bile salts break down large fat globules into smaller droplets, increasing their surface area and making them more accessible to lipase. This significantly enhances fat digestion.

The Interplay of Physical and Chemical Digestion

It's crucial to understand that physical and chemical digestion are intricately intertwined. Physical processes, such as chewing and peristalsis, prepare the food by breaking it down into smaller pieces, exposing a larger surface area for the action of enzymes. Chemical digestion, then, effectively breaks down the complex molecules into simpler forms that can be absorbed across the intestinal lining. They are not separate processes but rather two complementary aspects of a single, unified digestive system.

The Absorption of Nutrients

Once the food has been chemically broken down into its simplest forms (amino acids, monosaccharides, fatty acids, and glycerol), the nutrients are absorbed primarily through the walls of the small intestine. This absorption involves both passive and active transport mechanisms, ensuring that nutrients are efficiently transferred from the lumen of the intestine into the bloodstream and lymphatic system for distribution throughout the body.

Distinguishing Chemical and Physical Changes

To solidify the understanding, let's explicitly contrast chemical and physical changes in the context of digestion:

Physical Changes: These changes alter the form or appearance of a substance without changing its chemical composition. Examples in digestion include:

- Chewing (mastication): Food is physically broken down into smaller pieces, but its chemical composition remains unchanged.

- Peristalsis: Food moves through the digestive tract, changing its location, but not its chemical structure.

- Churning in the stomach: Food is mixed and broken down mechanically, but the molecules remain the same.

Chemical Changes: These changes involve the alteration of the chemical composition of a substance. Examples in digestion include:

- Action of salivary amylase: Starch is broken down into simpler sugars.

- Hydrochloric acid denaturing proteins: The protein structure changes, altering its function.

- Enzyme action in the small intestine: Proteins, carbohydrates, and fats are broken down into their building blocks.

The key difference lies in whether the chemical identity of the substances changes. Physical changes only alter the physical properties (size, shape, location), while chemical changes alter the molecular structure and create new substances.

Conclusion: A Coordinated Effort

Digestion is a marvel of biological engineering, a coordinated effort between physical and chemical processes that allows our bodies to extract essential nutrients from food. The mechanical breakdown of food increases the surface area, making chemical digestion more efficient. Conversely, chemical processes ensure the complete breakdown of complex molecules into simpler forms that can be absorbed and utilized by the body. Understanding the interplay between these two types of changes is fundamental to appreciating the intricate complexity and remarkable efficiency of the human digestive system. This knowledge also empowers us to make informed choices about our diet and overall health, emphasizing the importance of balanced nutrition for optimal digestive function.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How Many Legs Does A Bird Have

Mar 15, 2025

-

Lowest Common Multiple Of 9 12 And 15

Mar 15, 2025

-

What Is The Step Down Transformer

Mar 15, 2025

-

Whats The Difference Between Charcoal And Coal

Mar 15, 2025

-

Economists Say That The Allocation Of Resources Is Efficient If

Mar 15, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Digestion Of Food Is Chemical Or Physical Change . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.