What Is The Basic Unit Of A Protein

Juapaving

Mar 14, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

What is the Basic Unit of a Protein?

Proteins are the workhorses of the cell, carrying out a vast array of crucial functions. From catalyzing biochemical reactions as enzymes to providing structural support and acting as signaling molecules, their versatility is unparalleled. But what is the fundamental building block that allows proteins to achieve this remarkable functional diversity? The answer, simply put, is the amino acid.

Understanding Amino Acids: The Building Blocks of Proteins

Amino acids are organic molecules containing a central carbon atom (the α-carbon) bonded to four different chemical groups:

- An amino group (-NH₂): This group is basic and readily accepts a proton (H⁺).

- A carboxyl group (-COOH): This group is acidic and readily donates a proton (H⁺).

- A hydrogen atom (-H): A simple hydrogen atom.

- A side chain (R group): This is the variable group that distinguishes one amino acid from another. The R group's properties (size, charge, polarity, etc.) profoundly influence the protein's overall structure and function.

This simple yet elegant structure is the key to protein diversity. The sequence and arrangement of amino acids within a protein determine its three-dimensional structure and, consequently, its biological activity.

The Twenty Standard Amino Acids

There are twenty standard amino acids commonly found in proteins. These amino acids are encoded by the genetic code and are used by ribosomes during protein synthesis. They can be categorized based on their side chain properties:

-

Nonpolar, aliphatic amino acids: These amino acids have hydrophobic (water-repelling) side chains. Examples include glycine, alanine, valine, leucine, isoleucine, and methionine. These often cluster together in the protein's interior, away from the aqueous environment.

-

Aromatic amino acids: These amino acids possess aromatic ring structures in their side chains. Examples include phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan. They are often involved in interactions with other molecules, including light absorption in the case of tyrosine and tryptophan.

-

Polar, uncharged amino acids: These amino acids have hydrophilic (water-attracting) side chains that can form hydrogen bonds. Examples include serine, threonine, cysteine, asparagine, and glutamine. These often reside on the protein's surface, interacting with the surrounding water molecules.

-

Positively charged amino acids (basic amino acids): These amino acids possess positively charged side chains at physiological pH. Examples include lysine, arginine, and histidine. These can participate in ionic interactions and are often involved in enzyme-substrate binding.

-

Negatively charged amino acids (acidic amino acids): These amino acids possess negatively charged side chains at physiological pH. Examples include aspartate and glutamate. These also participate in ionic interactions, contributing to the protein's overall charge distribution.

Cysteine: A Special Case

Cysteine deserves special mention. Its thiol (-SH) group is highly reactive and can form disulfide bonds (-S-S-) with other cysteine residues. These disulfide bonds play a crucial role in stabilizing the three-dimensional structure of many proteins, particularly those secreted from the cell.

From Amino Acids to Proteins: The Peptide Bond

The amino acids are linked together through a peptide bond, a covalent bond formed between the carboxyl group of one amino acid and the amino group of another. This reaction releases a molecule of water (dehydration synthesis). A chain of amino acids linked by peptide bonds is called a polypeptide. A protein is essentially one or more polypeptide chains folded into a specific three-dimensional structure.

The sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain is determined by the genetic code, which is transcribed from DNA into messenger RNA (mRNA) and then translated by ribosomes into a polypeptide chain. This sequence, often referred to as the primary structure of a protein, dictates the higher levels of protein structure.

Levels of Protein Structure

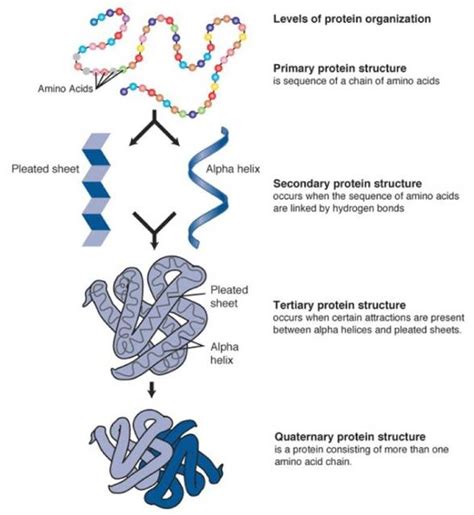

The three-dimensional structure of a protein is crucial for its function. This structure is hierarchical, consisting of four levels:

1. Primary Structure: The Amino Acid Sequence

The primary structure is simply the linear sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain. This sequence is determined by the genetic code and is crucial because it dictates all subsequent levels of structure. Even a single amino acid change can dramatically alter the protein's function, as seen in many genetic diseases.

2. Secondary Structure: Local Folding Patterns

The primary structure folds into local patterns stabilized by hydrogen bonds between the backbone atoms. The most common secondary structures are:

-

α-helices: Right-handed coiled structures stabilized by hydrogen bonds between the carbonyl oxygen of one amino acid and the amide hydrogen of an amino acid four residues away.

-

β-sheets: Extended structures formed by hydrogen bonds between adjacent polypeptide chains (or segments of the same chain). β-sheets can be parallel or antiparallel, depending on the orientation of the polypeptide chains.

-

Turns and loops: These are short, irregular segments that connect α-helices and β-sheets, contributing to the overall protein fold.

3. Tertiary Structure: The Three-Dimensional Arrangement

Tertiary structure refers to the overall three-dimensional arrangement of a single polypeptide chain, including its secondary structure elements. This structure is stabilized by various interactions between amino acid side chains:

-

Hydrophobic interactions: Nonpolar side chains cluster together in the protein's interior, minimizing their contact with water.

-

Hydrogen bonds: Polar side chains can form hydrogen bonds with each other or with water molecules.

-

Ionic bonds (salt bridges): Positively and negatively charged side chains can attract each other.

-

Disulfide bonds: Cysteine residues can form covalent disulfide bonds, further stabilizing the structure.

4. Quaternary Structure: Multiple Polypeptide Chains

Quaternary structure refers to the arrangement of multiple polypeptide chains (subunits) in a protein complex. Many proteins consist of two or more polypeptide chains that interact to form a functional unit. Hemoglobin, for example, is a tetramer composed of four polypeptide chains. The interactions between subunits are similar to those that stabilize tertiary structure.

Protein Folding and Misfolding

The process of protein folding is complex and not yet fully understood. However, it is known that proteins generally fold spontaneously into their native (functional) conformation, driven by hydrophobic interactions and other non-covalent forces. However, this process can be influenced by various factors, including chaperone proteins that assist in proper folding and prevent aggregation.

Protein misfolding can lead to the accumulation of misfolded proteins, which can disrupt cellular function and contribute to various diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and cystic fibrosis.

Conclusion: The Amino Acid's Central Role

In conclusion, the basic unit of a protein is the amino acid. The twenty standard amino acids, each with unique properties dictated by their side chains, are linked together by peptide bonds to form polypeptide chains. These chains then fold into complex three-dimensional structures, determined by the amino acid sequence and stabilized by various interactions. The understanding of amino acid structure and their interactions is pivotal to comprehend protein function, folding, and the implications of misfolding in disease. Further research continues to unravel the complexities of protein structure and function, leading to potential therapeutic interventions for protein-related diseases. The journey from amino acid to functional protein remains a fascinating area of biological investigation.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Which Of The Following Bonds Is The Weakest

May 09, 2025

-

Least Common Multiple Of 36 And 54

May 09, 2025

-

Compare And Contrast Weathering And Erosion

May 09, 2025

-

How Many Mm In 12 Cm

May 09, 2025

-

What Is 40 Percent As A Fraction

May 09, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Is The Basic Unit Of A Protein . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.