What Are The Building Blocks Of All Matter

Juapaving

Mar 09, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

What Are the Building Blocks of All Matter? A Deep Dive into the Fundamental Particles

The question of what constitutes the universe's fundamental building blocks has captivated humankind for millennia. From ancient philosophers pondering the nature of reality to modern physicists utilizing the most advanced technologies, the pursuit of understanding matter's composition continues to drive scientific inquiry. This article delves into the fascinating world of particle physics, exploring the building blocks of all matter and the forces that govern their interactions.

From Atoms to Subatomic Particles: A Journey into the Microcosm

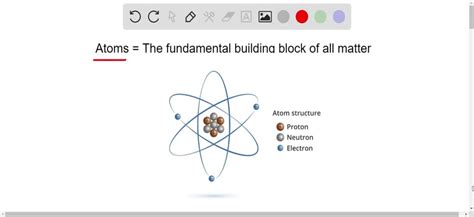

For centuries, the atom was considered the smallest indivisible unit of matter. The Greek word "atomos," meaning "indivisible," perfectly reflected this belief. However, advancements in scientific understanding, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, revealed a far more complex reality. Experiments like those conducted by Ernest Rutherford, using alpha particle scattering, unveiled the atom's internal structure: a tiny, dense nucleus surrounded by orbiting electrons.

This discovery shattered the notion of the atom as the ultimate building block. Instead, it revealed a world of subatomic particles, opening a Pandora's box of intricate interactions and fundamental forces. The nucleus itself wasn't elementary; it comprises protons and neutrons, which are further composed of even more fundamental particles.

The Standard Model: Our Current Understanding

Our current understanding of fundamental particles is encapsulated within the Standard Model of particle physics. This model, a remarkably successful theory, describes the fundamental constituents of matter and their interactions via four fundamental forces:

-

Strong Force: The strongest of the four fundamental forces, the strong force binds quarks together to form protons and neutrons. It's responsible for holding the nucleus together despite the electrostatic repulsion between positively charged protons. Its range is extremely short, confined essentially to the nucleus itself.

-

Electromagnetic Force: This force governs interactions between electrically charged particles. It's responsible for phenomena like light, electricity, and magnetism. Its range is infinite, although its strength diminishes with distance.

-

Weak Force: The weak force is responsible for radioactive decay, a process where unstable atomic nuclei transform into more stable ones. It plays a crucial role in processes like nuclear fusion in stars and is responsible for certain types of radioactive decay. Its range is even shorter than the strong force.

-

Gravitational Force: Gravity, the weakest of the four fundamental forces, is responsible for the attraction between objects with mass or energy. Although seemingly insignificant at the subatomic level, it plays a crucial role in shaping the large-scale structure of the universe. Its range is infinite.

Quarks: The Building Blocks of Protons and Neutrons

Within the Standard Model, quarks are fundamental particles that are the constituents of protons and neutrons. There are six types, or "flavors," of quarks:

- Up (u): Has a charge of +2/3

- Down (d): Has a charge of -1/3

- Charm (c): Has a charge of +2/3

- Strange (s): Has a charge of -1/3

- Top (t): Has a charge of +2/3

- Bottom (b): Has a charge of -1/3

Protons are composed of two up quarks and one down quark (uud), resulting in a net charge of +1. Neutrons, on the other hand, consist of one up quark and two down quarks (udd), resulting in a neutral charge. The strong force binds these quarks together within protons and neutrons.

Quark Confinement and Asymptotic Freedom

A crucial aspect of quark behavior is quark confinement. Quarks are never observed in isolation; they are always bound together to form composite particles called hadrons, such as protons and neutrons. The strong force becomes increasingly strong as quarks are pulled apart, making it impossible to isolate a single quark.

Conversely, asymptotic freedom describes the phenomenon where the strong force weakens at very high energies or short distances. This allows for calculations involving quarks at high energies, which are crucial for understanding high-energy collisions in particle accelerators.

Leptons: The Other Fundamental Fermions

Besides quarks, the Standard Model includes another class of fundamental particles called leptons. These particles, unlike quarks, do not experience the strong force. There are six types of leptons:

- Electron (e⁻): A negatively charged particle that orbits the nucleus in an atom.

- Electron Neutrino (νₑ): A neutral particle with very little mass and interacts weakly.

- Muon (μ⁻): A heavier cousin of the electron, with a negative charge.

- Muon Neutrino (νμ): A neutral particle associated with the muon.

- Tau (τ⁻): Even heavier than the muon, also with a negative charge.

- Tau Neutrino (ντ): A neutral particle associated with the tau.

Leptons, along with quarks, are categorized as fermions, a class of particles that obey the Pauli Exclusion Principle—no two identical fermions can occupy the same quantum state simultaneously. This principle is fundamental to the structure of atoms and the stability of matter.

Gauge Bosons: Mediators of the Fundamental Forces

The interactions between fundamental particles are mediated by gauge bosons, force-carrying particles. Each fundamental force has its own corresponding gauge boson:

-

Photons (γ): The mediators of the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless particles and travel at the speed of light.

-

Gluons (g): The mediators of the strong force. Gluons are massless and bind quarks together.

-

W and Z bosons (W⁺, W⁻, Z⁰): These massive particles mediate the weak force. Their large mass accounts for the short range of the weak interaction.

-

Graviton (G): The hypothetical mediator of the gravitational force. The graviton has not yet been experimentally observed. Its existence is predicted by several theories but remains unproven.

The Higgs Boson: Giving Mass to Particles

The discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012 was a monumental achievement in particle physics. This particle is associated with the Higgs field, a pervasive field that permeates all of space and interacts with other particles, giving them mass. Particles that interact strongly with the Higgs field acquire a larger mass, while those with weak interactions have smaller masses. The Higgs boson's discovery confirmed a crucial prediction of the Standard Model and provided further evidence for its validity.

Beyond the Standard Model: Unanswered Questions and Future Directions

While the Standard Model has been incredibly successful in explaining a vast range of phenomena, it doesn't provide a complete picture of the universe. Several crucial questions remain unanswered:

-

Dark Matter and Dark Energy: These mysterious components make up the vast majority of the universe's mass-energy content but are not accounted for by the Standard Model.

-

Neutrino Masses: The Standard Model initially predicted massless neutrinos. However, experiments have shown that neutrinos have tiny but non-zero masses, requiring extensions to the model.

-

The Hierarchy Problem: The vast difference between the strength of gravity and other fundamental forces remains unexplained.

-

Unification of Forces: The Standard Model describes four fundamental forces separately. A major goal of physics is to unify these forces into a single framework, potentially at very high energies.

These and other open questions are driving ongoing research in particle physics, with scientists pushing the boundaries of experimental and theoretical understanding. Future experiments at high-energy colliders, such as the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), will continue to explore the nature of fundamental particles and forces, potentially revealing new physics beyond the Standard Model. New theories, such as supersymmetry and string theory, attempt to address the limitations of the Standard Model and provide a more complete description of the universe's fundamental constituents and the forces governing their interactions.

In conclusion, the quest to unravel the building blocks of all matter is an ongoing journey of discovery. While the Standard Model provides a remarkably successful framework for understanding fundamental particles and forces, many mysteries remain, fueling continued research and the pursuit of a deeper understanding of our universe. The ongoing exploration into these fundamental aspects of reality promises to continue unveiling fascinating new insights into the universe's intricate tapestry.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Lowest Common Multiple Of 4 And 5

Mar 09, 2025

-

Is The Melting Of Ice A Physical Change

Mar 09, 2025

-

What Is The Unit Of Inertia

Mar 09, 2025

-

The Correct Name For The Compound N2o3 Is

Mar 09, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Is A Function Of The Nucleus

Mar 09, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Are The Building Blocks Of All Matter . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.