Proteins Are Polymers Of Amino Acid Monomers

Juapaving

Mar 04, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Proteins: Polymers of Amino Acid Monomers

Proteins are the workhorses of the cell, carrying out a vast array of crucial functions essential for life. From catalyzing biochemical reactions to providing structural support, their diverse roles are a testament to their remarkable structure. At the heart of this structural complexity lies a fundamental truth: proteins are polymers of amino acid monomers. Understanding this relationship is key to grasping the intricate nature of proteins and their biological significance. This article delves deep into the chemistry of amino acids, their polymerization into proteins, and the various levels of protein structure that dictate their function.

Amino Acids: The Building Blocks of Proteins

Amino acids, the monomers of proteins, are organic molecules characterized by a central carbon atom (the α-carbon) bonded to four distinct groups:

- An amino group (-NH₂): This group is basic, capable of accepting a proton (H⁺).

- A carboxyl group (-COOH): This group is acidic, capable of donating a proton (H⁺).

- A hydrogen atom (-H): A simple hydrogen atom.

- A variable side chain (R group): This is the unique component that distinguishes one amino acid from another, conferring distinct chemical properties.

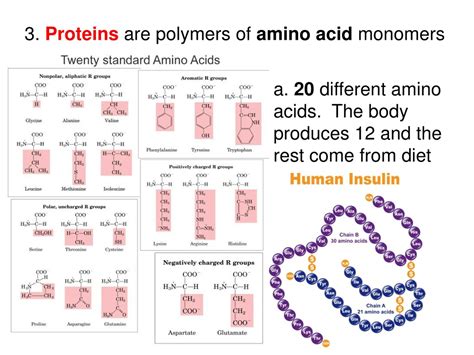

There are 20 standard amino acids encoded by the genetic code, each with a unique R group that influences its properties, such as size, charge, polarity, and hydrophobicity. These properties are crucial in determining the protein's overall three-dimensional structure and function.

Categorizing Amino Acids Based on R Group Properties

Amino acids can be broadly categorized based on the properties of their R groups:

1. Nonpolar, aliphatic amino acids: These amino acids have hydrocarbon side chains that are hydrophobic (water-repelling). Examples include glycine, alanine, valine, leucine, isoleucine, and methionine.

2. Aromatic amino acids: These amino acids possess aromatic rings in their side chains. They are generally hydrophobic, although their ring structures can participate in certain interactions. Examples include phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan.

3. Polar, uncharged amino acids: These amino acids have side chains that are hydrophilic (water-attracting) due to the presence of polar functional groups like hydroxyl (-OH) or amide (-CONH₂) groups. Examples include serine, threonine, cysteine, asparagine, and glutamine. Cysteine is unique due to the presence of a sulfhydryl (-SH) group, allowing the formation of disulfide bonds.

4. Positively charged (basic) amino acids: These amino acids have side chains with a positive charge at physiological pH. Examples include lysine, arginine, and histidine.

5. Negatively charged (acidic) amino acids: These amino acids have side chains with a negative charge at physiological pH. Examples include aspartic acid and glutamic acid.

Peptide Bond Formation: Linking Amino Acids

The polymerization of amino acids into proteins occurs through the formation of peptide bonds. This is a condensation reaction where the carboxyl group of one amino acid reacts with the amino group of another amino acid, releasing a water molecule. The resulting bond between the α-carbon of one amino acid and the nitrogen of the next is the peptide bond. This process creates a linear chain of amino acids, also known as a polypeptide.

The sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain is dictated by the genetic code. This sequence, known as the primary structure of a protein, is crucial in determining the higher-order structures and ultimately the protein's function. Changes in even a single amino acid can drastically alter the protein's properties and lead to malfunctions. This is exemplified in genetic diseases like sickle cell anemia, where a single amino acid substitution in hemoglobin leads to severe health consequences.

Protein Structure: From Primary to Quaternary

The remarkable functionality of proteins stems from their intricate three-dimensional structures. These structures are hierarchical, building upon each other from the linear sequence of amino acids.

1. Primary Structure: The Amino Acid Sequence

As mentioned, the primary structure is the linear sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain. This sequence is determined by the genetic code and dictates all subsequent levels of structure. The primary structure is held together by peptide bonds.

2. Secondary Structure: Local Folding Patterns

Secondary structures refer to local folding patterns within the polypeptide chain, stabilized primarily by hydrogen bonds between the carbonyl oxygen of one amino acid and the amide hydrogen of another. Common secondary structures include:

- α-helices: A coiled structure stabilized by hydrogen bonds between every fourth amino acid.

- β-sheets: Extended structures formed by hydrogen bonds between adjacent polypeptide chains (or segments of the same chain) arranged in a parallel or antiparallel fashion.

- Turns and loops: Short segments that connect α-helices and β-sheets, often containing glycine and proline residues.

The specific amino acid sequence strongly influences the formation of secondary structures. For example, proline, due to its cyclic structure, often disrupts α-helices.

3. Tertiary Structure: The Overall 3D Arrangement

Tertiary structure refers to the overall three-dimensional arrangement of a polypeptide chain, encompassing all secondary structure elements. This structure is stabilized by various interactions between amino acid side chains (R groups), including:

- Disulfide bonds: Covalent bonds between cysteine residues.

- Hydrophobic interactions: Clustering of nonpolar side chains in the protein's interior, away from the aqueous environment.

- Hydrogen bonds: Between polar side chains.

- Ionic bonds (salt bridges): Between oppositely charged side chains.

The tertiary structure is crucial for the protein's function, as it creates specific binding sites for ligands (molecules that bind to the protein) or active sites for enzymes.

4. Quaternary Structure: Multiple Polypeptide Chains

Some proteins consist of multiple polypeptide chains (subunits), each with its own tertiary structure. The arrangement of these subunits to form a functional protein is referred to as quaternary structure. These subunits are held together by the same types of interactions that stabilize tertiary structure. Examples of proteins with quaternary structure include hemoglobin and many enzymes.

Protein Function: A Diverse Array of Roles

The diverse functions of proteins are intimately linked to their unique three-dimensional structures. This structural diversity allows proteins to perform a vast array of tasks, including:

- Enzymes: Catalyze biochemical reactions.

- Structural proteins: Provide structural support, such as collagen in connective tissue and keratin in hair and nails.

- Transport proteins: Carry molecules across cell membranes, like membrane channels and carriers.

- Motor proteins: Generate movement, such as myosin in muscle cells and kinesin in intracellular transport.

- Hormones: Act as signaling molecules, like insulin and glucagon.

- Antibodies: Part of the immune system, recognizing and binding to foreign substances.

- Receptor proteins: Bind to signaling molecules, triggering cellular responses.

- Storage proteins: Store amino acids, like ferritin which stores iron.

Denaturation: Loss of Protein Structure and Function

Proteins are sensitive to changes in their environment. Factors such as temperature, pH, and the presence of certain chemicals can disrupt the weak interactions that stabilize protein structure, leading to denaturation. Denaturation results in the loss of the protein's three-dimensional structure and, consequently, its function. While some proteins can refold (renature) after denaturation, many are irreversibly damaged. This is why high fevers can be dangerous; they can denature essential proteins in the body.

Conclusion: The Interplay of Structure and Function

The statement "proteins are polymers of amino acid monomers" is more than just a simple chemical description; it's the foundation upon which an incredible diversity of biological function is built. Understanding the intricacies of amino acid structure, peptide bond formation, and the hierarchical levels of protein structure is paramount to grasping the fundamental mechanisms of life. The specific arrangement of amino acids dictates the protein's three-dimensional structure, which in turn, dictates its function. This intricate interplay between structure and function is what makes proteins such remarkable and essential molecules. The continuing study of proteins and their diverse roles remains a critical area of biological research, with implications for understanding diseases, developing new therapies, and advancing biotechnology.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Are Biotic Factors And Abiotic Factors

Mar 04, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Planets Has No Moon

Mar 04, 2025

-

The Swim Bladder Of Bony Fishes Functions In

Mar 04, 2025

-

What Is 3 5 As A Percentage

Mar 04, 2025

-

What Is The Difference Between Colonialism And Imperialism

Mar 04, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Proteins Are Polymers Of Amino Acid Monomers . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.