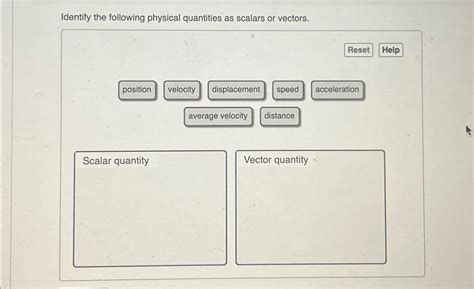

Identify The Following Physical Quantities As Scalars Or Vectors

Juapaving

Mar 12, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Identify the Following Physical Quantities as Scalars or Vectors: A Comprehensive Guide

Understanding the difference between scalar and vector quantities is fundamental in physics and many other scientific disciplines. While both describe physical properties, they differ significantly in how they are represented and manipulated mathematically. This article will delve deep into the distinction, providing a comprehensive list of physical quantities categorized as either scalar or vector, along with explanations and examples to solidify your understanding.

What are Scalar Quantities?

Scalar quantities are completely described by a single number (magnitude) and a unit. They possess only size or magnitude; they do not have a direction associated with them. Think of them as simple numerical values. Examples include:

- Mass: The amount of matter in an object. A mass of 10 kg is completely defined; no direction is implied.

- Speed: The rate at which an object covers distance. A speed of 60 km/h tells us how fast the object is moving, but not where it's going. (Contrast this with velocity, below).

- Temperature: A measure of hotness or coldness. 25°C describes a temperature without any directional component.

- Energy: The capacity to do work. 100 Joules of energy is a scalar quantity.

- Time: The duration of an event. 5 seconds is a scalar.

- Volume: The amount of space occupied by an object or substance. 10 liters of water is a scalar quantity.

- Density: Mass per unit volume. A density of 2 g/cm³ is a scalar.

- Work: The product of force and displacement in the direction of the force. While calculated from vectors, work itself is a scalar.

- Power: The rate at which work is done. 100 watts is a scalar quantity.

- Pressure: Force per unit area. 1 atmosphere of pressure is a scalar.

What are Vector Quantities?

Vector quantities, unlike scalars, require both magnitude and direction for complete description. They are often represented graphically as arrows, where the length of the arrow corresponds to the magnitude and the arrowhead points in the direction of the vector. Examples include:

- Displacement: The change in position of an object. A displacement of 10 meters east is a vector quantity. Note the crucial difference between displacement (a vector) and distance (a scalar): you could walk 20 meters and end up only 10 meters east of your starting point.

- Velocity: The rate of change of displacement. A velocity of 20 m/s north is a vector. This specifies both speed and direction.

- Acceleration: The rate of change of velocity. An acceleration of 5 m/s² upwards indicates both the magnitude and direction of the acceleration.

- Force: A push or pull exerted on an object. A force of 10 N to the right is a vector. This specifies the strength and direction of the push or pull.

- Momentum: The product of mass and velocity. Since velocity is a vector, momentum is also a vector.

- Weight: The force of gravity acting on an object. Weight is a vector pointing downwards.

- Electric Field: A vector field that describes the influence of a charged object on other charged objects.

- Magnetic Field: A vector field describing the influence of magnets and moving charges on other magnets and moving charges.

- Torque: The rotational effect of a force. It requires both magnitude (how much rotation) and direction (the axis of rotation).

- Angular Velocity: The rate of change of angular displacement.

Mathematical Representation and Operations

The mathematical treatment of scalars and vectors differs significantly. Scalars are manipulated using standard arithmetic operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division). Vectors, however, require more sophisticated mathematical tools:

Vector Addition and Subtraction

Vectors are added and subtracted using the rules of vector algebra. Graphically, this involves placing the tail of the second vector at the head of the first vector. The resultant vector is drawn from the tail of the first vector to the head of the second vector. This is known as the triangle law of vector addition. Alternatively, the parallelogram law can be used for the graphical addition of two vectors. Analytically, vectors are often represented in component form (e.g., using Cartesian coordinates), allowing for algebraic addition and subtraction of their individual components.

Scalar Multiplication

A vector can be multiplied by a scalar. This changes the magnitude of the vector but not its direction. If the scalar is negative, it reverses the direction of the vector.

Dot Product (Scalar Product)

The dot product of two vectors results in a scalar quantity. It is calculated by multiplying the magnitudes of the two vectors and the cosine of the angle between them. The dot product is useful for determining work done, for example.

Cross Product (Vector Product)

The cross product of two vectors results in another vector. The magnitude of the resultant vector is given by the product of the magnitudes of the two vectors and the sine of the angle between them. The direction of the resultant vector is perpendicular to the plane formed by the two original vectors, determined by the right-hand rule. The cross product is useful in determining torque and other rotational quantities.

Identifying Quantities: A Practical Approach

To determine whether a physical quantity is a scalar or a vector, ask yourself these questions:

- Does it have magnitude? All physical quantities have a magnitude (size).

- Does it have direction? If yes, it's a vector. If no, it's a scalar.

Let's test this with some examples:

- Energy: It has magnitude (Joules), but no direction. Therefore, it's a scalar.

- Force: It has magnitude (Newtons) and direction (e.g., upward, downward, left, right). Therefore, it's a vector.

- Temperature: It has magnitude (degrees Celsius or Fahrenheit), but no direction. Therefore, it's a scalar.

- Velocity: It has magnitude (speed) and direction (e.g., north, south, east, west). Therefore, it's a vector.

- Time: It has magnitude (seconds, minutes, hours), but no direction. Therefore, it's a scalar.

- Area: It has magnitude (square meters, square feet), but it is often associated with an orientation (e.g. the plane of a sheet of paper), but this is more about the geometric representation than an inherent vectorial property in the way velocity or force are. Generally considered a scalar in most contexts.

- Volume: Has magnitude (cubic meters) and no direction. Thus, it's a scalar.

- Angular momentum: This quantity combines mass, rotational speed, and distance from the axis. All three of these considerations are critical for determining angular momentum, and the directional consideration (axis of rotation) means this quantity is a vector.

Advanced Concepts and Applications

The distinction between scalar and vector quantities is not just an academic exercise; it's crucial for accurate physical modeling and problem-solving. Many physical laws and equations are expressed in vector form, highlighting the importance of direction in their applications. For instance, Newton's second law (F = ma) is a vector equation, implying that both force and acceleration are vector quantities, and their directions are linked.

Furthermore, the concept extends beyond classical mechanics to other areas of physics, including electromagnetism, fluid mechanics, and quantum mechanics. Understanding the mathematical operations associated with vectors is essential for solving problems in these fields. Vector calculus, a branch of mathematics, provides tools for analyzing vector fields, which describe how vector quantities vary in space. This is critical in understanding phenomena like fluid flow, electric and magnetic fields, and many other physical processes.

Conclusion

The categorization of physical quantities as scalars or vectors is a fundamental concept with far-reaching implications in science and engineering. This article provides a solid foundation for understanding the difference, including mathematical representation and applications. By mastering this distinction, you'll be better equipped to tackle more complex problems in physics and related fields. Remember, the key difference lies in the inclusion of direction: magnitude alone defines a scalar, while both magnitude and direction define a vector. This seemingly simple distinction is a cornerstone of many scientific endeavors.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is 1 Billion X 1 Trillion

May 09, 2025

-

Vinegar Is An Acid Or Base

May 09, 2025

-

What Is 3 Out Of 4 As A Percentage

May 09, 2025

-

Why Is The Chromosome Number Reduced By Half During Meiosis

May 09, 2025

-

How To Find Particular Solution Differential Equations

May 09, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Identify The Following Physical Quantities As Scalars Or Vectors . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.