Does Light Travel In A Straight Line

Juapaving

Mar 04, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Does Light Travel in a Straight Line? A Deep Dive into the Nature of Light

The simple answer to the question, "Does light travel in a straight line?" is: mostly, yes, but not always. This seemingly straightforward question opens a fascinating door into the complex and counterintuitive world of physics, revealing the intricate nature of light and its interactions with the universe. While the concept of light traveling in straight lines (rectilinear propagation) is a fundamental principle underlying many aspects of our everyday experience, a closer look reveals nuances and exceptions that challenge this basic understanding.

The Straight Path: Understanding Rectilinear Propagation

The idea that light travels in straight lines is a cornerstone of geometrical optics. This model simplifies the behavior of light, allowing us to understand phenomena like shadows, reflections, and refractions. We readily observe this in everyday life: a laser pointer creates a straight beam, and sunlight casts distinct shadows. These observations underpin the principle of rectilinear propagation, which states that light travels in a straight line in a homogeneous medium. A homogeneous medium is one that has uniform properties throughout, meaning the light doesn't encounter changes in density, refractive index, or other properties that might alter its path.

Examples of Rectilinear Propagation:

-

Shadows: The formation of sharp shadows demonstrates that light travels in a straight line from the light source to the object, and then the object blocks the light, creating a dark area behind it. The sharper the shadow, the more accurately it reflects the straight path of light.

-

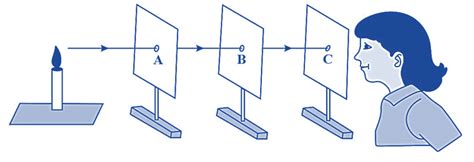

Pinhole cameras: A simple pinhole camera relies on rectilinear propagation. Light from an object passes through a small hole, projecting an inverted image onto a screen. The straight-line path of light is crucial to forming this image.

-

Laser beams: The highly collimated nature of laser beams is a testament to their ability to travel in remarkably straight lines over considerable distances. This is why lasers are used in surveying and other precision measurement applications.

The Bends and Twists: When Light Deviates from a Straight Path

While rectilinear propagation serves as a useful approximation in many scenarios, it's crucial to recognize its limitations. Several phenomena demonstrate that light doesn't always travel in a straight line. These deviations are governed by the wave nature of light and its interactions with matter.

1. Refraction: Bending Light with Different Media

Refraction is the bending of light as it passes from one medium to another, such as from air to water or glass. This bending occurs because the speed of light changes as it transitions between media with different refractive indices. The refractive index is a measure of how fast light travels in a given material. The greater the difference in refractive indices, the greater the bending of light. This principle is used in lenses, prisms, and fiber optics.

-

Lenses: Convex lenses converge light, focusing it to a point, while concave lenses diverge light, spreading it out. Both effects rely on the refraction of light at the lens surfaces.

-

Prisms: Prisms separate white light into its constituent colors (dispersion) because different wavelengths of light refract at slightly different angles.

-

Fiber optics: Fiber optic cables utilize total internal reflection, a phenomenon related to refraction, to guide light signals over long distances with minimal loss.

2. Diffraction: Light's Wave-like Nature

Diffraction refers to the bending of light as it passes around obstacles or through narrow openings. This phenomenon highlights the wave nature of light; light doesn't simply travel in straight lines, but rather spreads out, creating interference patterns. The amount of diffraction depends on the wavelength of light and the size of the obstacle or opening.

-

Single-slit diffraction: When light passes through a narrow slit, it doesn't just create a sharp image of the slit; instead, it spreads out, forming a diffraction pattern with a central bright fringe and weaker fringes on either side.

-

Diffraction gratings: These devices consist of many closely spaced slits, producing a more pronounced diffraction pattern, which is used to analyze the wavelengths of light.

-

Resolution limits in microscopes and telescopes: Diffraction limits the resolution of optical instruments; it sets a fundamental limit on how small objects can be resolved using light.

3. Interference: The Superposition of Light Waves

Interference occurs when two or more light waves overlap. Constructive interference occurs when the waves are in phase, resulting in a brighter light. Destructive interference occurs when the waves are out of phase, resulting in a dimmer light or even complete darkness. Interference patterns demonstrate the wave-like nature of light and can lead to deviations from a simple straight-line path.

-

Thin-film interference: This is responsible for the iridescent colors seen in soap bubbles and oil slicks, caused by the interference of light waves reflected from the top and bottom surfaces of the thin film.

-

Newton's rings: These circular interference patterns are formed when a plano-convex lens is placed on a flat surface, illustrating the interference of light waves reflected from the lens and the flat surface.

-

Holography: Holography uses interference patterns to create three-dimensional images.

4. Scattering: Light's Interaction with Particles

Scattering occurs when light is deflected by particles in a medium. The amount of scattering depends on the wavelength of light and the size and nature of the particles. Rayleigh scattering, where shorter wavelengths (blue light) are scattered more strongly than longer wavelengths (red light), explains why the sky is blue.

-

Atmospheric scattering: This explains why the sky appears blue and sunsets appear red.

-

Mie scattering: This type of scattering, caused by larger particles, is responsible for the hazy appearance of the atmosphere on polluted days.

-

Tyndall effect: The scattering of light by colloids (like milk or fog) is known as the Tyndall effect, making the beam of light visible.

5. Gravitational Lensing: Bending Light with Gravity

Einstein's theory of general relativity predicts that massive objects warp spacetime, causing light to bend as it passes near them. This effect, known as gravitational lensing, is observed around galaxies and galaxy clusters. The light doesn't literally bend; rather, its path is altered by the curvature of spacetime itself. This effect allows astronomers to observe objects that would otherwise be too faint or distant to see.

The Quantum Realm: Light's Dual Nature

The wave-particle duality of light complicates the simple notion of light traveling in a straight line. While light exhibits wave-like behavior in phenomena like diffraction and interference, it also behaves like a stream of particles (photons) in other instances, such as the photoelectric effect. This dual nature makes it challenging to assign a definitive path to a single photon. The concept of a trajectory becomes somewhat ambiguous in the quantum realm.

The Uncertainty Principle: Limits on Precision

Heisenberg's uncertainty principle states that it is impossible to simultaneously know both the position and momentum of a particle (including a photon) with perfect accuracy. This fundamental limitation implies that even if we assume light travels in a straight line, there's an inherent uncertainty in its precise path.

Conclusion: A nuanced perspective

In conclusion, the statement that light travels in a straight line is a useful approximation within the framework of geometrical optics, but it's an oversimplification. The true nature of light is far more complex, incorporating its wave-particle duality and interactions with matter and gravity. While light generally follows a straight path in a homogeneous medium, its behavior can be significantly altered by refraction, diffraction, interference, scattering, and gravitational lensing. Understanding these exceptions is crucial for a deeper appreciation of the fascinating and multifaceted nature of light. The more we delve into the intricacies of light, the more we realize that the seemingly simple concept of a straight-line path reveals a universe of complexity and wonder.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How Many Lines Of Symmetry Does A Rectangle Have

Mar 04, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Statements Is Correct

Mar 04, 2025

-

What Is The Square Root Of 121

Mar 04, 2025

-

How Many Inches Is 25 Cm

Mar 04, 2025

-

How Many Milliseconds In A Minute

Mar 04, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Does Light Travel In A Straight Line . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.